Republicans in Congress are working to pass a budget reconciliation bill that includes a range of dangerous and destructive proposals. In aggregate, the bill serves to transfers wealth to the nation’s richest individuals and corporate interests and is funded through a combination of deep cuts to social welfare programs, placing a staggering debt burden on future generations, and critically, through the mandatory sale of at least 2 million acres and up to 3 millions of acres of our public lands to private interests over the next 5 years.

Specifically, the Senate’s bill includes a proposal that makes 250 million acres of public land across 11 western states, including Washington, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming, eligible for sale to private interests. Parcels would be nominated by “any interested party” and offered for sale every 60 days until quotas are met.

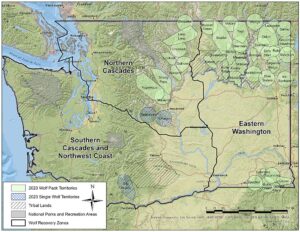

In Washington alone, over 5 million acres of our national forest and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land, including the majority of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, with the exclusion of a few designated areas such as Wilderness and the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, will be eligible for sale. This includes areas of mature and old-growth forests, critical wildlife habitat, and roadless areas, which are crucial to preserving habitat connectivity.

Legislative efforts to sell off public lands are not new. However, the current proposal to dispose of public lands is by far the largest and most brazen ever attempted. It is an effort to transfer public lands to a small number of private interests at the expense of the common good that is more reckless, aggressive, and destructive than anything we’ve seen before.

The time we have to stop it from passing is extremely limited. The bill could come to a vote on the floor as soon as next week before heading back to the House of Representatives.

Most of the proposals, including the sale of public land, that make up the Republican-backed budget reconciliation bill are broadly unpopular with voters across the political spectrum. Unfortunately, Republican Senate leadership are advancing the reconciliation bill within a compressed timeline that bypasses public input, offers minimal public notice, and lacks meaningful tribal engagement, thus circumventing normal democratic processes and norms.

This is possible because of special rules applied to budget reconciliation legislation, a unique type of legislation that only requires a 51 vote majority to pass in the Senate instead of the 60 vote majority typically needed to overcome filibusters.

In practical terms, this means that Senate Republicans’ proposals to auction off millions of acres of public lands could become law in mere weeks, with the first sales potentially beginning as soon as the end of summer. And this is all happening with no filibuster threat forcing compromise and negotiation, no consultation with the Tribes whose traditional and cultural use territories are being sold, no hearings, no debates, and no public input opportunities.

HOW TO HELP PROTECT PUBLIC LANDS

The situation is dire, but thankfully, the vast majority of public opinion is on our side. Selling public lands isn’t a divisive issue. Regardless of political party, the majority of American voters (including registered Republicans) in western states are overwhelmingly opposed to the sale of public lands to pad the pockets of the wealthy.

Republicans have a slim 3-vote majority in the Senate. If we can convince even a small number to stand against the unpopular sale of public lands, we can defeat this destructive proposal! By raising awareness and speaking out about the issue, we have a real chance to pressure Republican senators from western states to withdraw their support for the proposal that attacks public lands.

Public opinion contributed to the House’s decision to withdraw proposals to sell public land from its version of the bill, and public opinion can help defeat the proposal in the Senate as well.

It’s up to us to fight for our public lands! Here are 3 simple steps you can take today to help make a difference.

1. THANK SENATORS OPPOSING THE BILL AND ASK THEM TO SPEAK LOUDLY ABOUT THE ISSUE.

If you are a Washington or Oregon resident, thank your senators for opposing the bill, and urge them to speak out boldly against the sale of public lands.

2. TELL REPUBLICAN SENATORS IN WESTERN STATES TO PUSH BACK AGAINST UNPOPULAR PROPOSALS TO SELL OFF PUBLIC LANDS.

If you have a connection to, or use public lands in western states with Republican Senators (AK, ID, UT, WY), tell them to protect the places you care for. Public lands and the tourism they create support the economies of every western state, and these places belong to all of us, regardless of where we live.

3. HELP RAISE AWARENESS ABOUT THIS CRITICAL ISSUE

This is a tumultuous moment in time. Given the lack of public notice and the undemocratic measures the Senate is using to quickly advance the legislation, the sale of public lands could easily slip under the radar of many people who would be outraged to learn about what is happening. Share this blog post with your friends and family in other states—especially states with Republican senators. Ensure they understand the issue and know how to voice their support for public lands.

Email your Senators directly by clicking on this link. Choose your state and then select the “Contact” button under each Senator. You will have to send separate messages to each individually.

In addition to the information provided above, you can use these talking points to craft your message:

• Please protect the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and other cherished public lands by opposing the public land sell off provisions in the Senate reconciliation bill.

• Disposal of some of the lands that would be eligible for sale in the Senate’s proposal would violate the federal government’s legal and moral obligations to uphold rights guaranteed to various Tribes by treaties, for example rights to access traditional hunting and fishing areas within ceded territories. Furthermore, planning to quickly sell off any public lands, regardless of the existence of treaty rights for the parcels in question, without meaningful government-to-government consultation with Tribes and without providing Tribes with a first refusal is outrageous.

• Public lands and waters closest to cities are often heavily used and loved because they provide access to hunting, fishing, hiking, and other outdoor recreational activities close to home. Public lands and waters are a shared resource that provide the backbone of the outdoor recreation and tourism industry.

• Almost all of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest would be available for sale in the current Senate proposal. In addition to providing communities in SW Washington with critical resources and revenue from the sustainable management of forest products, the Gifford Pinchot is a critical stronghold for wildlife habitat we can’t afford to lose to private development.

• Public lands belong to the people. Selling off these lands to fund tax cuts for the wealthy and corporate interests with no real opportunity for input from the public is a stunning betrayal of the public good.

• Our public lands provide drinking water to millions of people. Drinking water for 1 in 5 people flows from Forest Service lands, and drinking water for 1 in 10 people flows from BLM lands. Public land sales of the type in this bill could put drinking water at risk.

• Allowing “any interested party” to nominate any of the 250 million acres of eligible public lands to be sold to private interests puts billionaires before the American people and is unacceptable. We should protect these landscapes for the benefit of all, including future generations.

• Selling off public lands that are far from any communities or housing infrastructure does not make sense and will not help create affordable housing.