[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]

By Hal Bernton

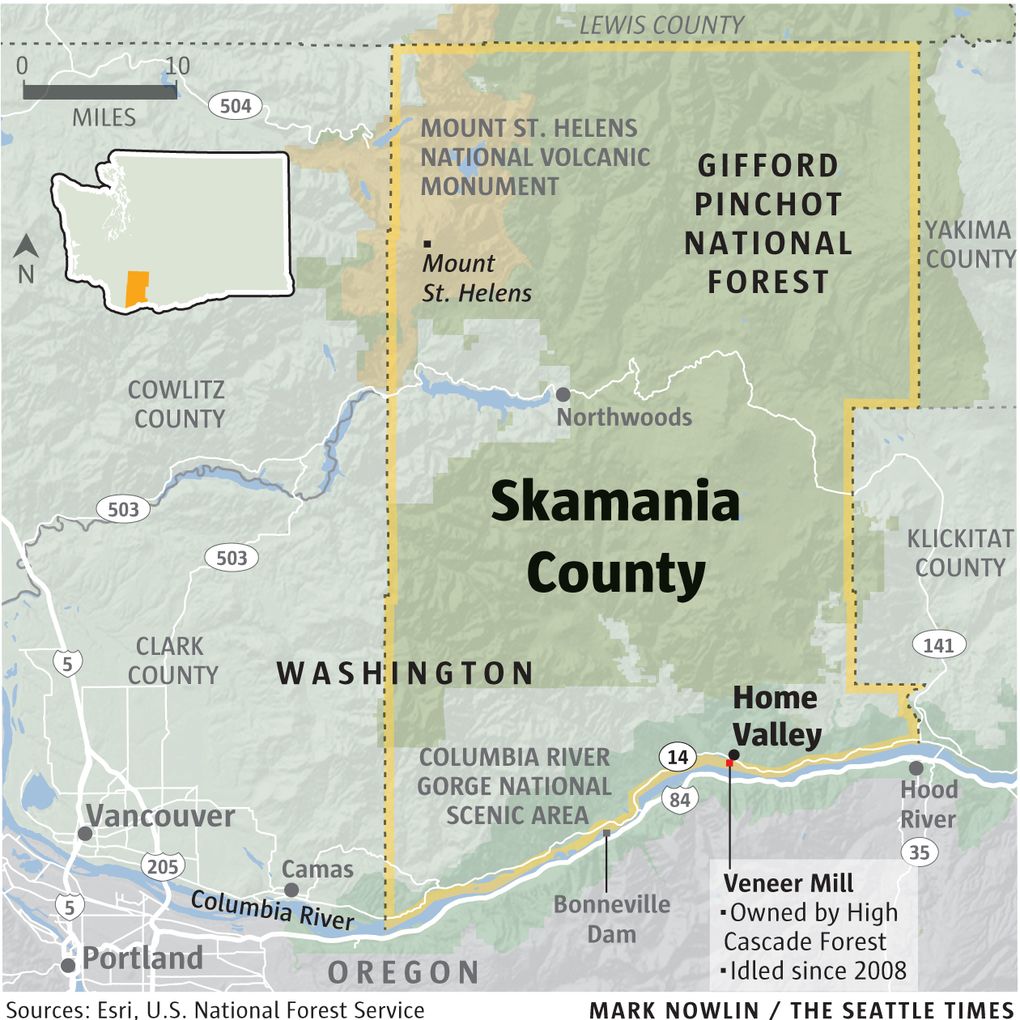

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_column_text]HOME VALLEY, Skamania County — The mill is idle now, but 30 workers used to turn logs into softwood veneer here in the heart of the Columbia River Gorge. They held down the kind of family-wage jobs that President-elect Donald Trump talked about reviving in campaign speeches that often included calls for rolling back environmental rules.

“Timber is a crucial industry in Oregon but it is being hammered, why are we surprised, by federal regulations,” Trump declared during a May stopover in Eugene, Ore.

So in the aftermath, what would it take for Trump to make good on his campaign talk, at least in this sliver of rural America, and bring the Home Valley mill back into operation?

These timber sales call for selective logging rather than stripping all the trees off a harvest site, as often happened in decades past.

In well-designed timber sales, this logging can serve a dual purpose. These selective harvests yield wood for mills, and let in more light to increase plant diversity in cutover lands that have regrown thick, tight stands of Douglas fir.

“A lot of these stands were planted as monocultures, and they need thinning,” said Matt Little, executive director of the Cascade Forest Conservancy, which focuses on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

James Peña, Pacific Northwest regional forester for the U.S. Forest Service, says collaboration on the Gifford Pinchot is part of a broader effort that has spread across Washington and Oregon forests. The work of some 35 groups involved doesn’t grab headlines, but it has helped to build trust — and a greater consensus — on how to manage these public lands.

“I see this as a way forward,” Peña said. “It doesn’t do us any good to go after (timber sale) projects that were just going to get wrapped up in litigation.”

On the Gifford Pinchot forest, so long as the collaborative process is not short-circuited, Little says he could envision higher numbers of trees each year coming off the forest.

For the mill to reopen, the cutting must include some of the older, bigger-diameter trees — typically around 60 years of age or more — that are needed to run veneer mills.

“Absolutely, I would like to see it open. I prefer the timber that builds our homes to be coming from local, sustainably harvested forests,” Little said. “It’s better for the local communities. And it’s better for the forest.”

Lost trust

During the last century, Skamania County enjoyed the kind of prosperity that Donald Trump seemed to be summoning up with his slogan “Make America Great Again.”

The economy was keyed to logging federal lands, which occupy about 80 percent of the land within the county of some 11,330 people.

From the middle of the century through the late 1980s, the annual harvests often were more than 10 times the current levels on the Gifford Pinchot.

In addition to all the timber and mill jobs, the county received a share of the federal logging revenue to bolster local government spending for schools and other services.

But the clear-cutting of centuries-old trees in federal forests ignited an epic environmental backlash. And timber sales were blockedby a lawsuit that sought protection for the spotted owl under the federal Endangered Species Act.

In 1994, under the Clinton administration, the Northwest Forest Plan set up major conservation measures that launched a new era of Forest Service management and reduced logging. Early in that decade, Skamania lost 10 percent of its job base, according to a state report, and unemployment reached 22 percent in February 1992.

Skamania County has struggled through a difficult transition away from a timber-based economy, more so than others in the Gorge.

In 2014, nearly 70 percent of earned income came from residents who commuted to jobs, and many of those who opted to stay closer ended up in low-paid work in the service industry.

“This town has definitely become reliant on tourism jobs,” said Heather Shields, 27, a waitress in the county seat of Stevenson. “Logging jobs are few and far between.”

Shields says she and most of her high-school friends voted for Trump, who ended up with 52 percent of the county vote compared with 39 percent for Hillary Clinton.

The shift to tourism also has not done much to make up for the downturn in timber revenue that flowed to the county, where less than 2 percent of its acreage is in a tax base of residential and commercial properties. And that has hit schools hard.

“My grandchildren don’t have the kind of extracurricular activities that there used to be. The schools can’t afford it,” says Lori Cochran, a clerk at the Home Valley Store across the highway from the mill.

To cobble together a budget, the county has become dependent on payments from Congress, which only partially compensate for the lost timber revenues.

As they scramble for money, Skamania’s three county commissioners have emerged as big critics of federal forestland management.

Two years ago, they passed a resolution declaring “a state of emergency” on federal forestlands They stated that they had lost trust in an agency they accused of “improperly avoiding and limiting” timber harvests.

Under a Trump presidency, Skamania Commissioner Chris Brong is hoping the Forest Service will give the county more say in managing the federal lands.

“We need to be on more of an equal footing, that would be my highest priority,” Brong said.

Finding the money

Though Gifford Pinchot logging is not expanding fast enough to suit the county commissioners, it is on the rise.

During the past six years, as the legal challenges have diminished, Gifford Pinchot National Forest timber-sale volumes have more than tripled, to 32.8 million board feet in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30.

To reopen the veneer mill, High Cascade would need to secure an additional 15 million board feet of federal timber.

“It has very good modern equipment. It’s just idle because we don’t have a supply of logs,” said Schneider, the High Cascade vice president.

That additional timber could come from the Gifford Pinchot without exceeding the conservation restrictions of the Northwest Forest Plan. But even if the collaborative process can fend off new lawsuits, the Forest Service would still need more funding to draw up the sales.

That’s been a big challenge.

Forest Service budgets have been consumed by billions of dollars spent to fight wildfires across the country. U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., helped lead a bipartisan effort to rework the budget so accounts that fund timber sales, recreation and other activities aren’t tapped to pay for putting out wildfires.

So far, there have been stopgap measures to shore up holes in the Forest Service budget. But unless there is action soon, the issue will await a new Congress and President Trump.[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”164,161,145″ img_size=”full” onclick=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]