Victory! We are pleased to announce that the U.S. Forest Service has listened to concerns raised by Cascade Forest Conservancy about the Upper Wind timber sale. Our efforts lead to the removal of more than 150 acres of mature stands of 120-year old trees from their proposal.

While this may seem like a small win in a time when victories in the fight to protect our climate are few and far between, its impact will last generations and it is still important to celebrate.

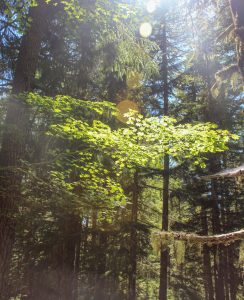

There is no ecologically-sound reason to harvest mature 120-year old trees; they are poised to be the next cohort of old-growth forests and to provide habitat that is critically lacking in the forests of the southern Washington Cascades. By protecting old-growth and soon-to-be-old-growth forests, we are safeguarding vital habitat for the many species that depend on these habitats, such as the iconic northern spotted owl and the rare fisher. Maintaining these unique ecosystems is also a vital component to addressing climate change. Compared to younger forests, large trees capture and store a disproportionate amount of carbon, and the cooler micro-climates they create are becoming important refuges for species working to adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

For the past two years, CFC has taken multiple approaches to oppose parts of the Upper Wind timber sale in the Mount Adams Ranger District (MARD) of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. This victory was achieved through collaboration, conversation, advocacy, and the help of people like you who commented during the project’s public feedback period required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Thank you!

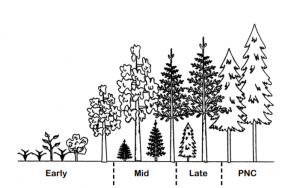

The process of planning timber sales on federally managed land often spans many years. To weigh in on projects as early as possible, CFC participates in Forest Collaboratives: organizations that bring together representatives of the Forest Service, Indigenous communities, timber companies, conservation organizations, rural communities, and outdoor recreation interests. It was over two years ago in a meeting of the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative (SGPC) that Forest Service representatives first floated the idea we came to oppose—creating a large amount of early seral habitat (forest characterized by the initial stages of regrowth following stand-replacing disturbances like fires and majors windstorms) using a clear-cutting method somewhat misleadingly referred to as regeneration harvest.

There is a need for early seral habitat on the landscape. Plants, animals, and other lifeforms have evolved to depend on and flourish in every stage of the natural cycle of destruction and renewal that characterizes forests in the Pacific Northwest. When the conversation in the SGPC about regeneration harvests began, the percentages of early seral on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest were on the low side.

Initially, these talks were theoretical because no actual proposal was on the table. We know that wildfire does a fantastic job of creating quality early seral habitats on the forest. We also know that–due to climate change–wildfire activity on our forests (especially in the east side forests that the MARD manages) is increasing. However, we didn’t know where the proposed creation of early seral via regeneration harvest would take place within the planning area, how old the potentially impacted trees were, or how big of a patch size they were targeting. The questions were whether achieving the quality of habitat early-seral-dependent species rely on is even possible without fires or other natural disturbances and, if so, what is the cost of creating this habitat with chainsaws instead of waiting for a natural disturbance?

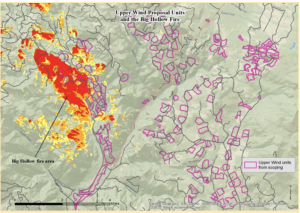

When CFC found out that the cost would be harvesting 152 acres of 120-year old trees, we opposed that portion of the proposal. In addition to expressing our concerns within the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative, CFC participated in further discussions by sitting in on the Zones of Agreement (ZOA) policy committee meetings. Even after the Big Hollow fire of 2020 resulted in more early seral than the agency had hoped to create, the Forest Service put forward an initial scoping plan that included large amounts of regeneration harvest in mature stands.

We responded by submitting comments representing the interest of our large base of supporters and worked to raise public awareness about the threat. Thanks to our collaborative relationships, advocacy work, and grassroots support, we stopped a major clear-cut without having to progress to further objections or lawsuits!

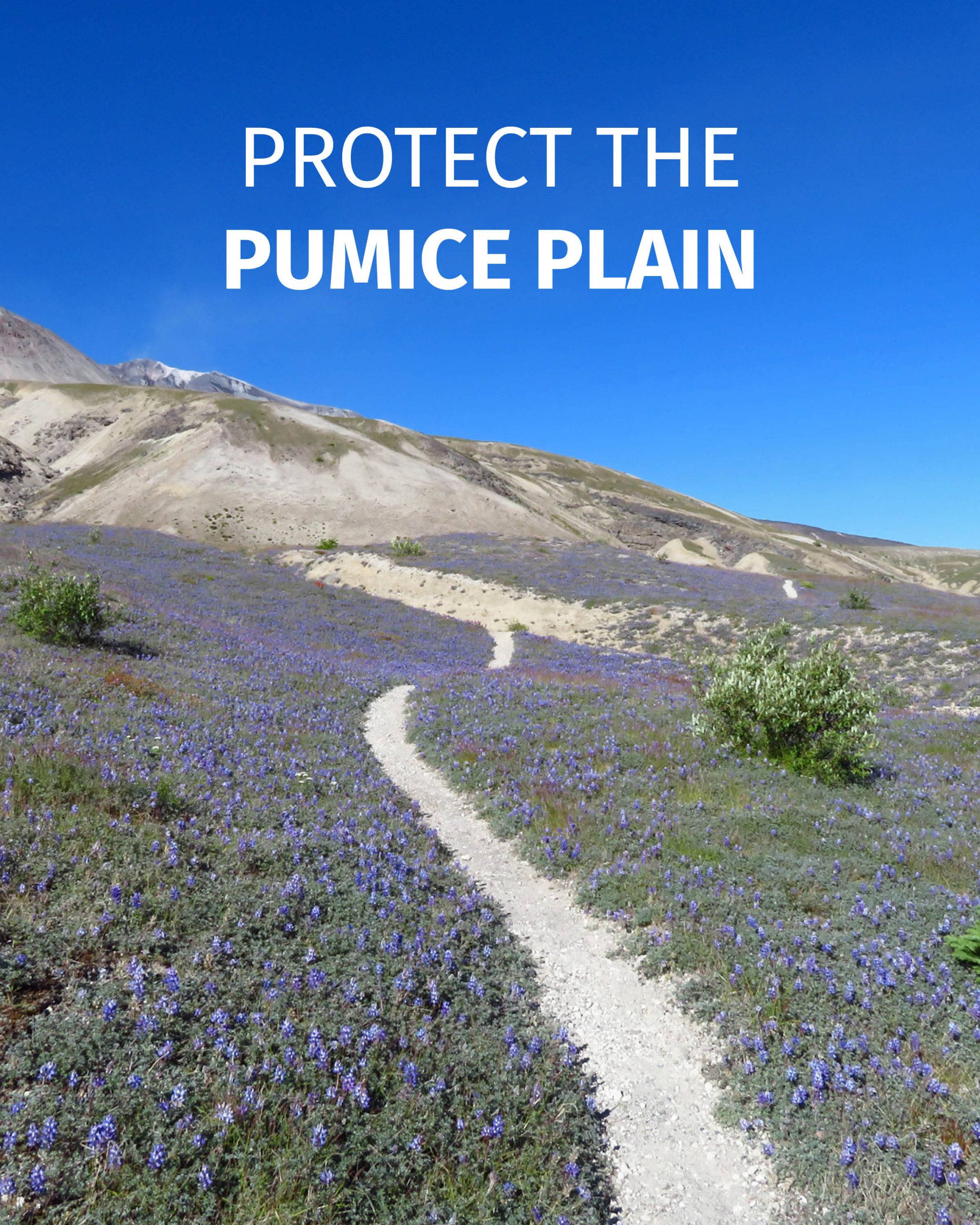

There are no small victories in the ongoing fight to protect old-growth and mature forests, to slow climate change, and to safeguard critical mature and old-growth habitats. We cannot allow these places to be sacrificed for economic gain or for unsustainable logging practices to be justified as tools for creating a habitat that is already becoming increasingly abundant due to the growing prevalence and severity of wildfires. To meet the challenges we are facing, climate policy and natural resource management need to progress toward respecting the latest science and prioritizing the protection of mature and old-growth habitats. However, we have reasons to be concerned that large-scale regeneration harvest proposals will still be proposed in the future.

Successfully removing these clear-cuts from the Upper Wind timber sale now is helping set an important precedent. In addition to protecting these specific trees, our work on the Upper Wind timber sale solidifies and demonstrates our policy stance to the agencies and organizations that Cascade Forest Conservancy works with. We do not support and WILL continue to oppose large-scale regeneration harvest (and any other cleverly-named clear-cuts) impacting old trees.

But

But