After building instream structures in a dry creek bed this past summer, we headed back to Stump Creek in early November to see how the structures faired following the first bout of rain. As we headed down to the project site, we saw new channels that had formed, sediment had built up behind structures, and huge, deep pools had appeared. And in those huge pools – we saw huge coho salmon!

Tributaries of large rivers provide off-channel spawning habitat that is critical for the end of an adult salmon’s life and their juvenile offspring. Stump Creek is a tributary that flows into the South Fork Toutle River, then into the Toutle River, Cowlitz River, Columbia River, and ultimately to the Pacific Ocean. That’s roughly 100 miles of waterways that these adult salmon travel to the ocean to grow big and then back to freshwater to spawn. Their journey from Pacific Ocean to Stump Creek is completely undammed, which is a rarity for anadromous fish to encounter. We are luckily seeing a movement to get more dams removed in the Pacific Northwest to restore access to more historical spawning grounds.

The fish that make it to Stump Creek in the winter are met with a flowing stream and many reaches with spawning gravel. Once the fry hatch, they have plenty of water to swim and forage. By the time August roles around, the creek begins to dry up, leaving juvenile salmon stranded in small pools. During the past two summers we have been at Stump Creek, we have found many dried out stream reaches that have piles of desiccated salmon fry. For this reason and it’s degraded state caused by anthropogenic and natural disturbances, Stump Creek has been a high priority for CFC and project partner, Lower Columbia Fish Enhancement Group.

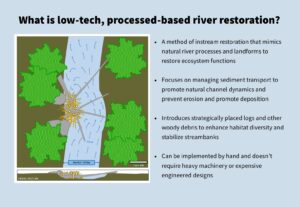

A LOW-TECH, PROCESS-BASED APPROACH

Following the promising results from last year’s successful Pilot Phase CFC staff and volunteers spent three weekends in August and September working to complete Phase 1 of our restoration plan for Stump Creek.

During the Pilot Phase and Phase 1, we worked to restore and improve this important fish habitat using a low-tech, process-based approach.

COMPLETING PHASE 1

Given the impacts we observed from the Pilot Phase, we were excited to add more wood to the stream. Over the course of three weekends, we installed a total of 32 structures along 1500 feet upstream of the Pilot Phase.

The first group of volunteers and staff arrived at the site in August and found a situation similar to what we had encountered the year before; dried-out stream reaches and fish stranded in tiny pools. We didn’t assume our first ten structures would completely fix Stump Creek, but the sight we encountered reiterated the huge need for more woody debris to help enhance and restore the system.

Our first team of volunteers worked hard in sweltering heat under hazy skies to construct the first 12 structures upstream from the Pilot Phase. These structure types ranged from:

- beaver dam analogs – wood structures that most closely resemble a beaver dam, used on smaller, less powerful side channels

- channel process structures – larger wood structures made from numerous alder logs and slash that were built up on one side of the bank to promote the movement of water to the opposite side of the structure

- channel spanning structures – larger beaver-esque structures made of numerous alder logs and slash that hold back sediment and create large pools

- habitat cover structures – tops of the alder trees that are placed over the stream to provide cover for our aquatic friends

The second weekend of work brought nicer weather and an even bigger group of volunteers! They managed to finish up the rest of the structures for a total of 32 structures. A few weekends later, a handful of volunteers and I went to put some finishing touches on the structures, set up wildlife cameras so we could watch the system change through time, and create a few extra habitat cover structures to try and help the dozens of fish that still remained in the tiny pools.

ENCOURAGING EARLY RESULTS

A final staff trip was conducted on November 10th. It had been raining for weeks, so it was time to see how the structures were holding up. We started by checking out the structures constructed during the 2022 Pilot Phase. As we’d observed earlier in the year, water in the Pilot Phase area was spreading all over the landscape and creating new channels.

We headed west toward the Phase 1 structures. We first passed several of our larger channel process and channel-spanning structures. Not only were they all in place, they were directing water in the direction and manner we had designed them to when we planned the project!

As we went further upstream, we came to our BDA section that we created on a side channel of Stump Creek. Our four BDAs that were working exactly as designed. We had created four cascading pools and spread the water outside of the previously confined channel. It was the perfect habitat for salmon!

So perfect in fact, that it was where we saw the first adult coho salmon of the day! We ended up seeing numerous other adult coho salmon utilizing the habitat enhancements our structures created. Some of them were swimming in the pools formed by the BDAs, others were preparing their redds (gravel bed to lay eggs) for spawning, and another was headed up stream to find find a location to spawn.

It was an incredibly rewarding sight. The lives of these coho would end here in Stump Creek, but their eggs are currently being incubated and will hatch in the next month or so. Once they do, our instream structures will be there to provide habitat for the new juvenile coho until they swim to the ocean.