Halfway through a day of collecting seeds from native plant species from forests north of Trout Lake, volunteers and CFC staff enjoyed a break with a unique view. Pahto (Mt. Adams) towered above an expanse of charred snags arranged among a green carpet of wildflowers, shrubs, berries, and new saplings flourishing in the abundant sunlight.

This area burned in 2015’s Cougar Creek Fire. Yet, seven short years later, it is well on its way to recovery and is currently providing valuable early seral habitat (areas characterized by the early stages of forest re-growth which are important to many plant and animal species) to the larger forest ecosystem. In dry mixed-conifer stands, like those found throughout the eastern half of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, wildfires are a natural and even necessary part of forest ecology. But not every fire-impacted area in this part of the forest is doing as well as this one.

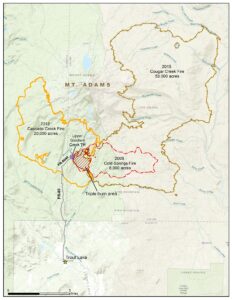

In some instances, climate change has led to more intense wildfires and shorter intervals between burns occurring in the same stands. These high-intensity, low-interval fires can deplete buried seedbanks and the forest’s ability to replenish and rely on the supply, making it difficult for some stands to recover naturally. Not far from where we were enjoying our break another fire-impacted area is fairing much differently. The triple burn area was affected by three fires in a short period of time–2008’s Cold Spring Fire, 2012’s Cascade Creek Fire, and the 2015 Cold Creek Fire. This area is now struggling to recover, so CFC’s staff, the US Forest Service, and volunteers are stepping in to lend a hand through what could be called “assisted migration” of vegetation from healthy stands to areas that have been slow to regrow.

For the past 6 years, we have been working to gather seeds from native plant species like beaked hazelnut, wax currant, snowberry, western columbine, pearly everlasting, ocean spray, lupine, wild roses, Oregon sunshine (aka wooly sunflower), and many others. We collect these materials from forests closely resembling the triple burn area in species composition and elevation. The collected seeds are then being used to revegetate the area where seedbanks have been exhausted.

Guided by Evan Olson, a botanist for the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, volunteers learned how to identify, collect, and label seeds from targeted species, and spent a beautiful sunny Saturday gathering among the understory.

Leading up to the trip, volunteers were given several documents to get a chance to familiarize themselves with the history of the three fires that created the triple burn area and a resource guide of native plant species that we would be encountering in the field. At each site we visited, volunteers and staff split into groups and dispersed throughout the area to find the seeds. Some worked as generalists collecting any species listed in the pre-trip materials they came across. Others specialized in finding one or two species.

At the end of the day, we gathered around Evan’s Forest Service pickup and handed over the last of our haul to be sorted, stored, and then used in upcoming revegetation efforts, including our upcoming and final volunteer trip of the year where many of the same seeds gathered will be spread throughout the triple burn area.

“This is vital work,” Evan explained as he thanked the volunteers for their efforts. Climate change may be altering the ecology of wildfire and the landscape’s ability to regenerate after a burn, but helpful interventions like these can make a long-lasting difference.