By Michal Orczyk | Development Director

April 22, 2020

Today is Earth Day, and it’s a special one: today we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of this historic moment in American history, which has now become a global phenomenon. Many people know about Earth Day, but those who weren’t around in 1970 might not know its origins. It is an amazing story that shows how grassroots activism, as well as courageous political leaders (sorely lacking in our day) can make sweeping changes in our world.

In American government and society, some initial discourse about human impacts on the environment began in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Writers like John Muir popularized a romantic vision of nature and wilderness, and how human values were sometimes in conflict with nature. National parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite were established in 1872 and 1890 respectively, and the idea of wilderness as a valuable part of the American landscape began to be appreciated (though indigenous people understood this long before). However, it wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century that scientists, naturalists and activists started to raise considerable alarm over the impacts of human industry on wildlife, landscapes, and our own health. Concepts like air and water pollution, biodiversity, and climate change began to take hold. One watershed moment was the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which sold over 500,000 copies in 24 countries.

In the late 1960s Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson was inspired by the student environmental movement, and announced the idea for a teach-in on college campuses to the national media. He also persuaded Pete McCloskey, a conservation-minded Republican congressman, to serve as his co-chair. They chose April 22, a weekday falling between Spring Break and final exams, to maximize the greatest student participation.

Dennis Hayes, a young activist and the organizer of this teach-in, realized the potential for this event to gain traction, and turned it into a national campaign that quickly drew massive media attention. Soon there were events planned in towns and universities across the United States. Nearly 20 million Americans took part! A high school senior in Portland convinced Oregon Governor, Tom McCall, to deliver a speech to an audience at his school, Fremont Junior High School (today Parkrose Middle School).

(Oregon Governor Tom McCall speaking at an Earth Day event in 1970. Source: Oregon Historical Society)

Earth Day 1970 achieved a rare political alignment, enlisting support from Republicans and Democrats, rich and poor, urban dwellers and farmers, business and labor leaders. By the end of 1970, the first Earth Day led to the creation of the United States Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of other first of their kind environmental laws, including the National Environmental Education Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and the Clean Air Act. Two years later Congress passed the Clean Water Act. A year after that, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act and soon after, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. These laws have protected millions of men, women and children from disease and death and have protected hundreds of species from extinction. (Source: https://www.earthday.org/history/)

CFC had big plans for Earth Day 2020, and due to COVID-19 we have to change some of those. However, we’d like to thank the organizers of Earth Day Oregon for bringing together hundreds of Oregon businesses and nonprofits to share a message – we must protect our home, our planet, from our own reckless behavior. Check out https://earthdayor.org/ to learn more about this wonderful state-wide campaign. Special thanks to our Earth Day Oregon 2020 business partners:

Chinook Book

Aesthete Tea

Jam on Hawthorne

Falling Sky Brewing

Oregon Data

By the 1990s, the use of ‘citizen science’ began to take off and there was an increase in the number of citizen projects, the variety of projects, and the size and scope of projects. Volunteers were being used across all fields and disciplines–making important contributions everywhere from astronomy to oceanography and everything in between. Today the number of citizen science participants have grown even more thanks to technological advancements. Advances like the internet and the creation of mobile smartphones have not only made information easier to obtain, but have created new ways for researchers to engage with large groups of people. For scientists who rely on data collected from the field, smartphones and their connectivity to the internet and their internal global positioning systems have greatly increased the ease of collecting data anywhere in the world. Volunteers are making huge contributions to our knowledge, whether gathering data from their own backyards or in the most remote places of the forest.

By the 1990s, the use of ‘citizen science’ began to take off and there was an increase in the number of citizen projects, the variety of projects, and the size and scope of projects. Volunteers were being used across all fields and disciplines–making important contributions everywhere from astronomy to oceanography and everything in between. Today the number of citizen science participants have grown even more thanks to technological advancements. Advances like the internet and the creation of mobile smartphones have not only made information easier to obtain, but have created new ways for researchers to engage with large groups of people. For scientists who rely on data collected from the field, smartphones and their connectivity to the internet and their internal global positioning systems have greatly increased the ease of collecting data anywhere in the world. Volunteers are making huge contributions to our knowledge, whether gathering data from their own backyards or in the most remote places of the forest.

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World

All That the Rain Promises and More…

All That the Rain Promises and More…

Desert Solitare

Desert Solitare The Book of Fire

The Book of Fire Sea and Smoke: Flavors from the Untamed Pacific Northwest

Sea and Smoke: Flavors from the Untamed Pacific Northwest The Man Who Planted Trees

The Man Who Planted Trees

A Walk in the Woods

A Walk in the Woods The Lorax

The Lorax Indians of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coming of the White Man to the Present Day

Indians of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coming of the White Man to the Present Day Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave like Humans

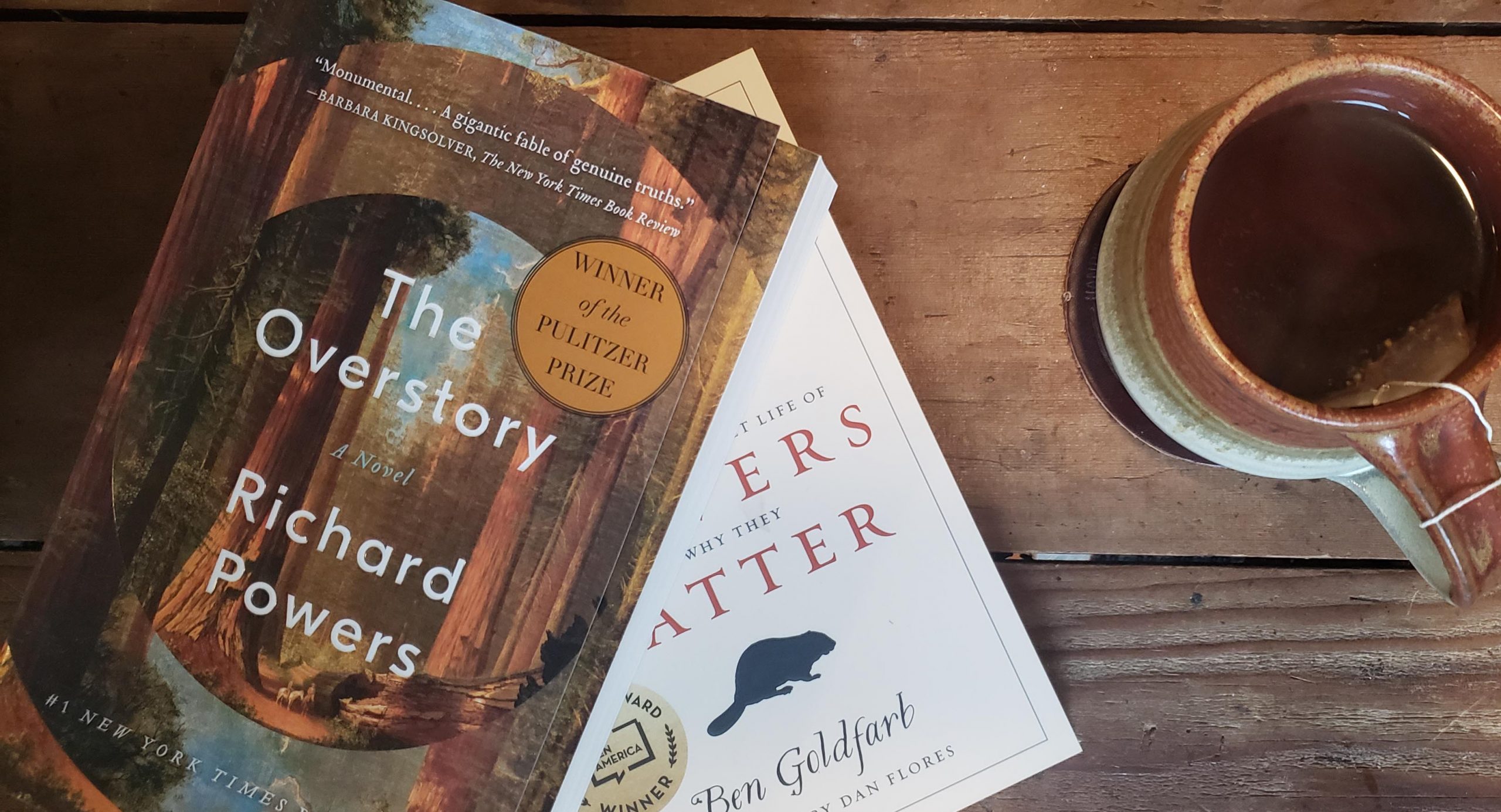

Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave like Humans The Overstory: A Novel

The Overstory: A Novel Inside Passage: A Journey Beyond Borders

Inside Passage: A Journey Beyond Borders Ever Wild: A Lifetime on Mount Adams

Ever Wild: A Lifetime on Mount Adams Sand County Almanac

Sand County Almanac Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Dark Divide

Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Dark Divide The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America

The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America The Invention of Nature

The Invention of Nature  Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast

Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast The Poetic Inventory of Rocky Mountain National Park

The Poetic Inventory of Rocky Mountain National Park

The US Forest Service has put forward plans to build a road through the heart of this irreplaceable landscape. The proposed road is a threat to the area’s streams, rivers, and lakes. If built, this road will pass over five permanent streams and 10 seasonal streams which together represent five separate watersheds, wholly created after the 1980 eruption. Pristine newborn watersheds like these do not exist anywhere else on earth. The proposed road would lead to soil erosion and deliver harmful sediment into streams and, subsequently, into Spirit Lake. Worse still, each stream-crossing would likely wash out every season, requiring excavation and rebuilding. All this sediment will force aquatic insects and fish to move downstream, negatively impact water quality, and damage stream and lakebed habitats.

The US Forest Service has put forward plans to build a road through the heart of this irreplaceable landscape. The proposed road is a threat to the area’s streams, rivers, and lakes. If built, this road will pass over five permanent streams and 10 seasonal streams which together represent five separate watersheds, wholly created after the 1980 eruption. Pristine newborn watersheds like these do not exist anywhere else on earth. The proposed road would lead to soil erosion and deliver harmful sediment into streams and, subsequently, into Spirit Lake. Worse still, each stream-crossing would likely wash out every season, requiring excavation and rebuilding. All this sediment will force aquatic insects and fish to move downstream, negatively impact water quality, and damage stream and lakebed habitats.