NEWS RELEASE | March 25, 2024

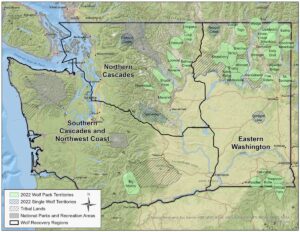

Vancouver, WA – Cascade Forest Conservancy, a Vancouver-based conservation nonprofit, is objecting to plans for the upcoming Yellowjacket timber sale, which will occur on national forest lands in Lewis and Skamania counties east of Mount St. Helens in the Camp Creek-Cispus River and Yellowjacket Creek watersheds. The conservation group says that the Forest Service provided inadequate analysis about certain aspects of the project, which they argue could result in harm to sensitive species and waterways in the forest. Plans for the proposed project include a total of 4,651 acres of timber harvest in addition to other infrastructure and habitat improvement activities.

Ashley Short, Cascade Forest Conservancy’s Policy Manager, said the Forest Service’s analysis of the timber sale’s impacts on waterways was conducted at a level that was too broad. “Analysis this broad hides what’s really going on at the various places affected by a project like this and ignores what could happen to specific waterways and sensitive species if Cascade Forest Conservancy didn’t speak up,” she said, adding that failing to object could contribute to a bad precedent regarding the level of analysis the agency applies to future projects.

Cascade Forest Conservancy’s objection, authored by Short and filed on Friday, March 22, argued that the agency’s plans for the timber sale failed to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires federal agencies to provide site-specific analysis for impacts resulting from actions taken on public land, but “instead rolled site-specific impacts into a larger watershed, diluting the true impacts of the project.”

According to Short, the Forest Service may choose to allow certain impacts to result from timber sales, but are obligated to study those impacts and present their analysis to the public for comment and engagement first.

Molly Whitney, Cascade Forest Conservancy’s Executive Director, says the conservation group has a positive working relationship with the Forest Service and expressed optimism that the concerns raised in her organization’s objection would be resolved without the need for litigation. Parties who object to timber sales discuss their concerns at an objection mediation meeting with the Forest Service.

“In this instance, the Forest Service failed to provide adequate site-specific analysis relating to the impacts of logging activities near several important streams. There is reason to believe that some of the streams located near timber stands where the agency is planning high-intensity harvest activities contain rare and sensitive species, like the Cascade torrent salamanders. We want the agency to provide the site-specific analysis required by law and that is needed to fully understand and address the impacts of this sale on places like Pinto and Stepladder Creek.” Said Whitney. “We want to see a specific analysis of how sedimentation from timber harvest activities will impact these waterways and the species depending on them. And we are asking the agency to address any site-specific negative impacts they find by reducing the intensity of timber harvest in certain areas.”

######