Monday, March 22

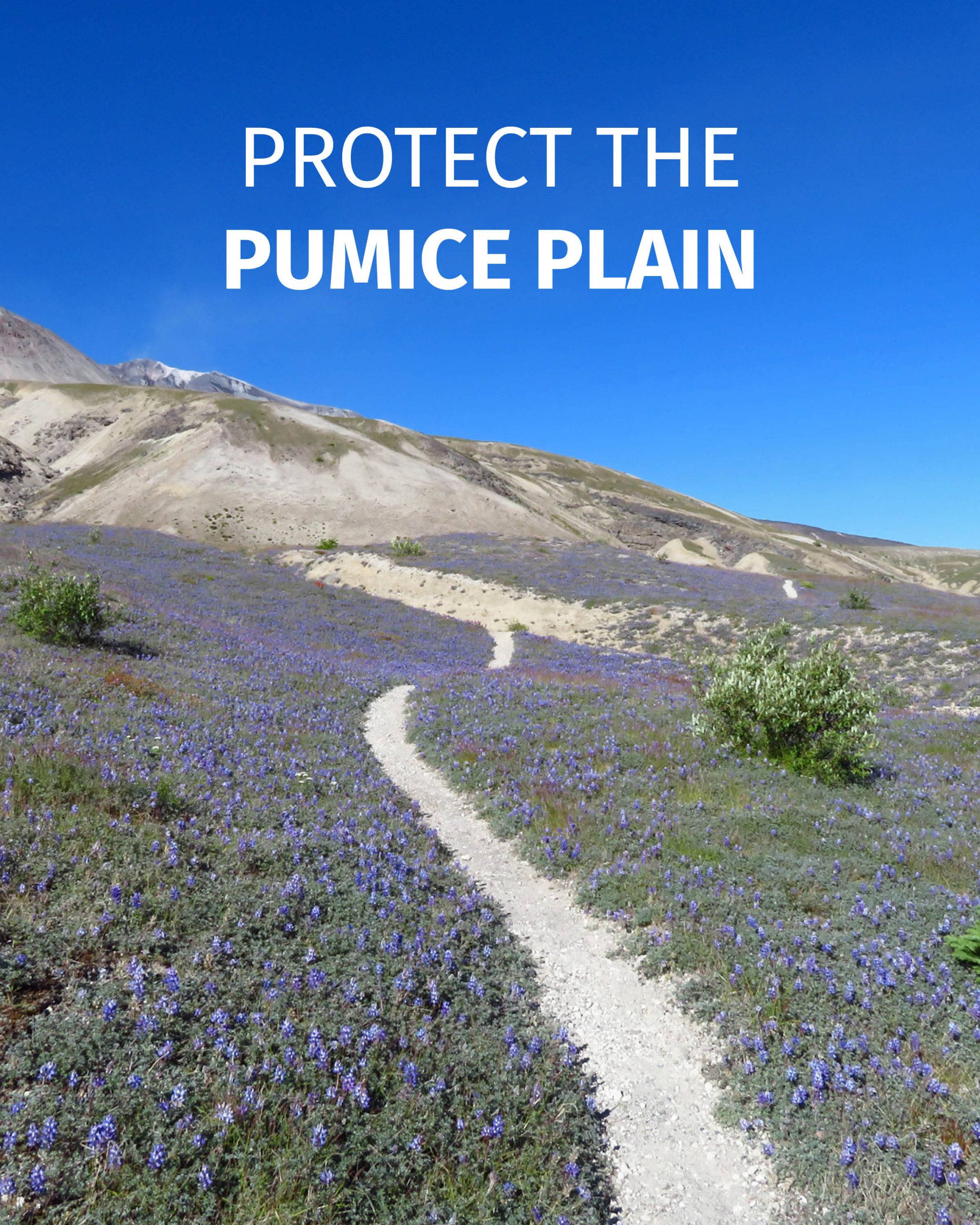

Today, Cascade Forest Conservancy and a coalition of scientists and conservation groups challenged in federal court a U.S. Forest Service plan to build a road through the Pumice Plain, the blast zone of Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, to assess the integrity of a natural dam on Spirit Lake created by the volcano’s eruption in 1980. The road would end dozens of irreplaceable scientific research projects, many dating back 40 years to just after the eruption, by destroying research plots and permanently changing the unique ecological conditions in the vicinity.

“Callous land managers are seeking to exercise dominion over the landscape at Mount St. Helens, but this landscape is more than just special, and more than just delicate,” said Susan Jane Brown, staff attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center, and Cascade Forest Conservancy Board Director. “The Pumice Plain is teaching the world new things we couldn’t learn in any other way, in any other place, which is what Congress intended when it created the National Volcanic Monument. Prudent planning can achieve a win for everyone: to ensure public safety while preserving this scientific jewel and the future discoveries that require its continued existence.”

The 1980 eruption provided scientists and researchers a unique and rare opportunity to study ecosystem recovery and formation, available nowhere else on earth. Nearly all aspects of terrestrial and aquatic ecology are under investigation at Mount St. Helens generally and on the Pumice Plain and in Spirit Lake specifically. This research could prove enormously beneficial to science, nature, and even to society.

Many ongoing studies rely on a single plot at the location of the first known plant to establish on the Pumice Plain, which was found to host a previously unknown species of moth. The proposed route for the road would go directly through this plot, destroying it and forestalling the insights it would provide us about biodiversity and landscape regeneration.

“Over the past four years, we have offered the Forest Service many alternatives to this project that protect public safety, preserve research plots on the Pumice Plain, and mitigate environmental impacts. Instead, the agency is pushing this project forward without adequate environmental analysis, or consideration of the permanent impacts the construction of a road will have on this incredible landscape,” said Lucy Brookham, Policy Manager for the Cascade Forest Conservancy. “Our members will see 40 years of research destroyed, recreation in a no-longer roadless landscape permanently altered, as well as the progress of newly forming wildlife, watersheds, and plant species halted in their tracks.”

In addition, the project would build a road on top of the Truman Trail, one of the most popular hiking trails in the Monument. This road would damage newly forming streams and watersheds, introduce invasive species, and severely detract from the experience of hikers on the only trail that connects public access from Johnston Ridge to Windy Ridge across the Pumice Plain.

The safety of residents downstream of Spirit Lake is extremely important, which is why thoughtful planning is essential. However, the Forest Service has not yet developed a comprehensive approach to ensuring the safety of downstream communities as well as protecting the internationally known research occurring at Mount St. Helens. Instead, the agency is piecemealing its management of this area. The Forest Service must achieve the shared goal of ensuring public safety while maintaining the Congressionally designated purpose of the monument: scientific study and research

“Insights from the scientists working at the monument inform ongoing restoration projects across Washington. Further understanding of these processes will be permanently destroyed if the proposed project is implemented as planned” said Becky Chaney, conservation chair of the Washington Native Plant Society. “The work is significant enough for WNPS to help fund the research through its grant program. The science on recovery and succession has resource and restoration applications to the conservation of native plants, to wildlife habitat recovery, and to my own work as a forest planning consultant.”

I was born a few years after the eruption of Mount St. Helens. The two five-gallon buckets of fine gray ash stored in our garage were curiosities I mostly ignored as I explored the seemingly ageless mountains, streams, and forests of the Pacific Northwest. They were certainly interesting–not only because of the stories associated with them, but also because their weight seemed alien, as if the contents of the buckets was at once too light and too heavy. In my mind, the Pacific Northwest had always been a place defined by peace and stillness. But as that ash attested to, the Pacific Northwest is in fact a place of incredible power and violence, of death and rebirth, destruction and transformation.

I was born a few years after the eruption of Mount St. Helens. The two five-gallon buckets of fine gray ash stored in our garage were curiosities I mostly ignored as I explored the seemingly ageless mountains, streams, and forests of the Pacific Northwest. They were certainly interesting–not only because of the stories associated with them, but also because their weight seemed alien, as if the contents of the buckets was at once too light and too heavy. In my mind, the Pacific Northwest had always been a place defined by peace and stillness. But as that ash attested to, the Pacific Northwest is in fact a place of incredible power and violence, of death and rebirth, destruction and transformation.

The US Forest Service has put forward plans to build a road through the heart of this irreplaceable landscape. The proposed road is a threat to the area’s streams, rivers, and lakes. If built, this road will pass over five permanent streams and 10 seasonal streams which together represent five separate watersheds, wholly created after the 1980 eruption. Pristine newborn watersheds like these do not exist anywhere else on earth. The proposed road would lead to soil erosion and deliver harmful sediment into streams and, subsequently, into Spirit Lake. Worse still, each stream-crossing would likely wash out every season, requiring excavation and rebuilding. All this sediment will force aquatic insects and fish to move downstream, negatively impact water quality, and damage stream and lakebed habitats.

The US Forest Service has put forward plans to build a road through the heart of this irreplaceable landscape. The proposed road is a threat to the area’s streams, rivers, and lakes. If built, this road will pass over five permanent streams and 10 seasonal streams which together represent five separate watersheds, wholly created after the 1980 eruption. Pristine newborn watersheds like these do not exist anywhere else on earth. The proposed road would lead to soil erosion and deliver harmful sediment into streams and, subsequently, into Spirit Lake. Worse still, each stream-crossing would likely wash out every season, requiring excavation and rebuilding. All this sediment will force aquatic insects and fish to move downstream, negatively impact water quality, and damage stream and lakebed habitats.