[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]

The Cascade Forest Conservancy (CFC) has grown a special partnership with the Cowlitz Indian Tribe (CIT) on a number of important projects. The Tribe has been a partner of ours for many years, collaborating in the field as well as on natural resources policy issues, but now we are rolling up our sleeves for several on-the-ground restoration projects. Most recently, the Cowlitz Tribe has been a key partner on our beaver reintroduction efforts, and a sub-grantee of a CFC Wildlife Conservation Society grant. This exciting collaboration is a major, landscape-scale restoration project in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest that grew out of our 2016 Wildlife and Climate Resilience Guidebook (which can be viewed here – https://www.cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Wildlife-and-Climate-Resilience-Guidebook-2017.pdf).

To date, CIT has collaborated with us on many pivotal aspects of the project – joining us on beaver habitat surveys, forming agreements with wildlife trapping companies to gather the beaver, and creating holding facilities to keep the beaver comfortable until they can be relocated.

Over the next year, CFC and CIT will continue to work closely to capture and relocate beavers from private lands, where they are often trapped and killed, to wild places where they help provide crucial functions to vulnerable waterways. Beaver’s industrious nature leads them to expand wetlands and fish habitat, create pools where water can cool down and slow down, and combat other effects of climate change. We are grateful to the Wildlife Conservation Society for giving us the opportunity to pursue this ambitious and important project.

Our work with the Cowlitz Tribe doesn’t end there. A forest-wide effort to restore huckleberry to the landscape is currently in its second year. The U.S Forest Service, Pinchot Partners Collaborative Group, CFC, CIT, and other agencies have worked together to create the first draft of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest Huckleberry Management Strategy. The strategy will be a guide for future huckleberry management by the Forest Service to ensure huckleberries are healthy and plentiful each season for pickers of all types.

Finally, we are very excited that a representative of the Cowlitz Tribe working on cultural resources is considering joining our Board of Directors. His background as an ecologist makes him a great addition to our Board and we look forward to bringing our two organizations closer through his involvement.

Our mission is to protect and sustain the forests, rivers, wildlife, and communities in the heart of the Cascades. The Cowlitz people are one of the communities that we are proud to call friends and partners. Together, we will continue to preserve the lands, history, and natural resources that are so important to our families and future generations.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Protecting the Unique Environment of Mount St. Helens

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens drastically altered the landscape of Southwest Washington in a matter of moments. A massive debris avalanche, formerly the north side of the mountain, crashed into Spirit Lake and careened down the Toutle River. The blast from the eruption destroyed ancient forests and covered the lands near the volcano in a layer of ash and pumice.

History of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument

In 1982, Congress created the 110,000 acre Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument to protect the unique research and recreation opportunities of this landscape. The heart of the Monument, and the research conducted there, is the Pumice Plain – where nothing survived the eruption.

May 18th was the thirty-eighth anniversary of the eruption, and throughout this time the Pumice Plain has been the site of several, long-term scientific studies. Thousands of people visit the Monument each year to witness the on-going return of plants and animals, and how the environment has changed in the years since the eruption.

Since the Monument’s creation, the Forest Service has allowed limited public access to the areas most impacted by the eruption, including the Pumice Plain. For example, to protect the natural recovery of the Pumice Plain, and the on-going long-term scientific research, no motorized vehicles are allowed. Even the Forest Service does not currently operate motorized vehicles on the Pumice Plain. Instead, they utilize helicopters when they need to access areas like Spirit Lake, as they have done for over three decades.

Proposed Motorized Access Routh Threatens the Pumice Plain

The Forest Service is now proposing a long-term administrative motorized access route across the Pumice Plain which risks this important landscape. The Forest Service’s stated need for this access route is to maintain the Spirit Lake Tunnel.

During the 1980 eruption, a debris flow blocked the natural outflow of Spirit Lake. Communities downstream were at risk of flooding if Spirit Lake were to overflow, so the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers created the Spirit Lake Tunnel to maintain safe water levels in Spirit Lake. The tunnel was completed in 1985, and the Forest Service has maintained the tunnel by helicopter ever since.

While we recognize the important need to balance protecting scientific, ecological, and recreational values with public safety, we remain concerned that the Forest Service has not adequately considered the long-term impacts of motorized administrative access across the Pumice Plain.

Especially concerning are the potential impacts of this motorized access route to ongoing, long-term scientific research. The Forest Service has not pointed to specific situations where they were unable to perform required maintenance on the tunnel, or that would prevent them from using helicopters for access as they currently do.

The Monument, especially the Pumice Plain, is a national treasure and world-renowned for scientific research. It is concerning to see the Forest Service consider an action that would damage this irreplaceable landscape without adequate analysis of whether this access route is necessary.

So far, we haven’t heard any evidence that the Forest Service now needs this motorized access to maintain the tunnel, when they have been successfully managing Spirit Lake water levels to protect downstream communities for over thirty years.

Help us continue our work to protect public lands in the Cascade Mountains by volunteering your time or becoming a CFC member.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

MINING AGAIN THREATENS MOUNT ST HELENS AREA

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]

Mining Again Threatens Mount St Helens Area Wild Fish and Habitat

By Matt Little, Cascade Forest Conservancy

Originally published in The Osprey Newsletter, May 2018

Download a PDF copy of the article by clicking HERE.

Just north of Mount St. Helens lies the beautiful and pristine Green River valley, which is a treasured wild steelhead refuge and a destination for backcountry recreationists. It is also the site of a proposed gold and copper mine, and a battle that has been raging for over a decade.

The headwaters of the Green River lie in a steep and verdant valley in the remote northeastern portion of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument and contain one of the world’s unique ecosystems. Following Mount St. Helens’ 1980 eruption, this valley had areas that were scorched by the blast and other areas that were sheltered and where old growth forests survived the volcanic catalysm. This resulting mix of native flora and fauna at various levels of succession created a mosaic of diversity that today supports a diversity species from wildflowers to herds of elk, and enjoyed by recreationists from bird-watchers to anglers.

The Green River flows in and out of the Monument’s borders, snaking its way west through the glacial-carved landscape of Green River valley. Further downstream, it flows into the famous Toutle/Cowlitz River system. From the Cowlitz Trout Hatchery and North Toutle Hatchery down to the Columbia River, this popular stretch provides anglers with abundant opportunities to catch salmon and steelhead. What many anglers don’t know, however, is that above this system flow waters so clean, clear, and productive for wild steelhead that the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife designated it in 2014 as one of the state’s first “Wild Stock Gene Banks”, to protect the integrity of the genetic stock. The Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board also identified the Green and North Fork Toutle Rivers as “Primary” waters — their highest designation — for the recovery of fall Chinook and coho salmon, and winter steelhead, in the lower Columbia River Basin. The clean water and habitat values of the Green River, and proximity to the scenic Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, also led the US Forest Service to determine that the Green River is eligible for Wild and Scenic River designation.

The valley is a treasure trove for other backcountry pursuits as well. It is a valuable wildlife corridor for the seasonal migration of a large elk herd, long recognized by the state wildlife agency for its habitat values. It also contains the Norway Pass special permit area for elk, highly coveted by hunters. Outdoor enthusiasts often start their adventures at the Green River Horse Camp to hike, bike, or ride horses along the 22-mile Goat Mountain and Green River loop trails through blast zone and old growth forests, and past beautiful alpine lakes and mountain views.

Enter Ascot Resources Ltd. This Canadian-based mining company has plans to explore for an industrial-scale mine in this valley. However, they are not the first prospectors to the area. In 1891, two German immigrant farmers were on a fishing and hunting expedition and found evidence of precious metals. This set off a mining rush in the area and led to the establishment of the Green River mining district in 1892 (later named the St. Helens mining district) to manage the numerous claims. However, these mining ventures proved to be unprofitable, and by 1926, the three companies that had explored the Green River valley deposits (called Mount Margaret) had failed. The gold rush had ended.

The latest search for industrial-scale gold and copper started in 1969 when Duval Corporation acquired the Mount Margaret mining rights and drilled 150 core samples in the 1970s. Following the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, Duval sold their claims to the Trust for Public Land. For over a decade, there was little interest in mining in the Green River valley until 1993, when Vanderbilt Gold Corp. applied for a mining permit in the area. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) concluded that mineral concentrations in the area were too low to be profitable and denied the permit.

In 2004, Idaho General Mines, Inc. (later known as General Moly Inc.) acquired a 50% interest in the Mount Margaret deposit and applied for a hardrock mining lease. The local conservation group, Cascade Forest Conservancy (CFC), then called the Gifford Pinchot Task Force, responded by rallying support from the community. The cities of Longview, Kelso, and Castle Rock, which depended on the Green and Toutle Rivers for their drinking water supplies, all passed resolutions against the mine proposal. During the public comment period for the mining permit’s Environmental Assessment, over 33,000 people expressed their concerns about the proposal. In 2008, the BLM denied the lease.

In March of 2010, the Canadian-based mining company, Ascot Resources Ltd., purchased the mining rights from General Moly Inc. In a very short time, and without an environmental assessment, the Forest Service approved Ascot’s drilling plan. By August the company had drills in the ground taking core samples. CFC requested an injunction and stopped the drilling by the summer of 2011. Ascot Resources quickly submitted a new permit in late 2011, which this time the Forest Service and BLM approved. However, CFC prevailed in 2014 when a federal court invalidated the permits and the parties withdrew their appeals.

Not to be discouraged, Ascot started writing another application in 2015. In January of this year, the Forest Service yet again approved the permit and passed it along to BLM for their review and concurrence. It is likely the agency will concur with the decision very soon, making it final.

An industrial-sized mine in the Green River valley would be catastrophic for fish, wildlife, and recreation. These types of mines often require huge open pits to process the amount of rock and minerals necessary to be profitable. They also require massive containment ponds held back by earthen dams to hold the toxic materials and heavy metals left in the tailings sludge after mining, including copper, lead, cyanide, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic. These “ponds”, are notorious for leaking or failing over time. If one of these is built in the steep Green River valley, which is in a seismically active area in the shadow of an active volcano, the earthen dams are almost guaranteed to fail. In 2014 a tailings dam at British Columbia’s Mount Polley Mine failed, destroying whole salmon rivers with toxic sludge. Nobody wants this to happen to the Green River.

A leak containing even the smallest amount of dissolved copper can disrupt a salmonid’s olfactory senses, and at 2.3–3.0 mg/L it can be lethal. Heavy metals not only impact fish, but they build up in the living tissue of organisms as they travel up the food chain and affect just about every living creature in the ecosystem, including humans. Mercury is notorious for this and is a potent neurotoxin, greatly affecting the nervous system.

Exploratory drilling alone can have significant impacts to fish and recreation along the Green River. Ascot Resources has plans to perform test drilling at 23 drill pads that will create 63 boreholes. The drills use chemical additives during the drilling process and a bentonite-based grout afterwards that can have impacts to groundwater and surface waters. The closest drilling sites are just 150 feet from Green River tributaries and others are approximately 400 feet from the Green River itself. Also, trees will be removed and formerly closed roads will be reconstructed, which will further impact the streams and fish.

Drilling, truck traffic, and other activities will create 24/7 noise throughout the summer into mid-fall, the same time of year that people visit this area for backcountry recreation and solitude. Bow season for elk and deer begins in September and the proposed mining site is the where most backcountry trips begin, since it is the end of the road and it is where the horse camp and trails begin. The fishing experience would certainly be disrupted, as well as the direct impacts to other fish and wildlife from the project itself.

A large coalition of recreation and conservation groups have partnered with the Cascade Forest Conservancy to oppose this mine. The Clark Skamania Flyfishers (CSF), established in 1975, is one of the most vocal opponents of the mine because of potential impacts to the local fishery. In a powerful video about the mine on Cascade Forest Conservancy’s website, CSF’s Steve Jones is documented fly fishing the Green River and talking about the inevitable impacts that mining will have on the 14-16 pound steelhead he loves. Others opposed to the mine include the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, the original owners and managers of this land, and even the Portland-based rock band Modest Mouse, who currently has an ad out against the mine on their main webpage.

All these calls to action have been heard by decision makers, including leaders in Congress. Washington’s Democratic Senator Maria Cantwell is an important ally for mine opponents, especially through her role as Ranking Member on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. In a 2016 Committee hearing on the Forest Service budget, Senator Cantwell grilled the former Chief of the Forest Service, Thomas Tidwell, on his agency’s insufficient review of this mine and the impacts it will have on the valley.

Ironically, all of the 900 acres currently under consideration for exploratory drilling were once owned by the conservation-focused Trust for Public Land (TPL), who had purchased it from Duval. In 1986, following the creation of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, TPL donated and sold their land and the mining rights to the Forest Service. During the land transfer, TPL wrote that they expected that the mineral rights “would be removed from entry under the General Mining Laws.” Fortunately, some of these lands were also purchased using money from the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF).

The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act was established by Congress in 1964 to use money generated from off shore oil and gas leases to acquire lands for conservation and recreation purposes. Since its inception, LWCF has protected over five million acres of conservation and recreation lands across the country. A mine established on these lands would be devastating not only to the Green River valley, but for public lands everywhere.

So what’s next? The Cascade Forest Conservancy and its coalition partners will continue to fight drilling in the Green River valley, including through more litigation if necessary. The coalition hopes for a permanent end to mining in this valley and is asking our leaders in Congress to lead a solution that will preserve the area’s exceptional fish populations, wildlife habitat, and backcountry recreation opportunities. The Land and Water Conservation Fund has strong bipartisan support, and any solution should also preserve the integrity of this law and the public lands it has protected.

The Green River valley is unique, and the fish, wildlife, and communities that depend on it for their livelihoods deserve our long-term support and protection. To learn more about this proposal and see a video of this beautiful landscape, go to https://cascadeforest.org/our-work/mining/. Also, please consider joining the Cascade Forest Conservancy as we work toward the long-term preservation of this treasured watershed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Changes to Federal Forest Policy in 2018 Spending Bill

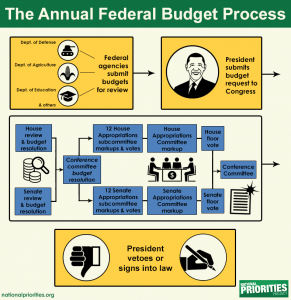

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”94″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” qode_css_animation=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_column_text]At the end of March Congress passed an appropriations bill over 2,200 pages long that allocated $1.3 trillion dollars to many government programs and agencies. This massive bill also included legislation that directly impact our public lands by addressing funding for wildfires and a new categorical exclusion (CE) that allows some timber sales to move forward with less environmental review. This new CE and other policy changes in this bill are attempts to weaken our environmental laws and limit public input on our federal forests, and we must remain ready to oppose further harmful riders in future bills.

What is the appropriations bill?

A bill that is over 2,200 pages long, concerning over a trillion dollars, and written in complicated legislative language, can seem overwhelming to many of us. This large bill specifies how much money will go to different government programs and agencies for fiscal year 2018.

Congress is required by law to pass twelve appropriations bills allocating discretionary spending for each fiscal year, which starts on October 1. However, since Congress was unable to come to an agreement on these bills in 2017, they extended the process through March 23 through “continuing resolutions” which provide temporary funding for federal agencies and avoid a government shutdown while Congress works through the appropriations process. This spending bill is large because it is an omnibus bill that combines the twelve funding areas.

extended the process through March 23 through “continuing resolutions” which provide temporary funding for federal agencies and avoid a government shutdown while Congress works through the appropriations process. This spending bill is large because it is an omnibus bill that combines the twelve funding areas.

Appropriations bills must be passed because without them, many government agencies and programs go unfunded and must shutdown. The importance of these bills makes them a target for riders, provisions that are unrelated to federal spending but are often added onto federal spending bills. Riders are a tactic used to enact legislative changes that would be difficult to pass on their own.

How does this bill impact our public lands?

For our public lands, some of the best news comes from what is not in the bill. Thanks to the dedication of concerned citizens throughout the country, some of the worst forest management provisons were not added to the bill. Portions of the Westerman Bill, including new categorical exclusions allowing timber harvest with little environmental review, had the potential to be added to this bill as riders. Another rider would have allowed reckless logging and road-building in roadless areas in Alaska’s national forests by exempting these forests from the 2001 Roadless Rule. Exempting millions of acres of public lands in Alaska from the Roadless Rule could have set a dangerous precedent for developing roadless areas throughout the U.S.

Although several harmful environmental riders did not make it into the bill, one that did is a new categorical exclusion (CE) for hazardous fuels reduction projects up to 3,000 acres. These are projects where the agencies propose reducing wildfire risk through commercial timber harvest. New CEs for timber harvest projects are concerning because CEs limit public input and environmental review. Instead of going through the normal public input process, which involves preparing an environmental assessment and multiple public comment periods, the agencies would only have to provide public notice and one comment period. To use this CE, the Forest Service must maximize the retention of old-growth and large trees and use the best available science to maintain and restore ecological integrity. Also, these projects must be developed collaboratively, not include permanent road construction, and be located outside wilderness and other protected areas. Commercial timber harvest to reduce fuels is potentially controversial in areas with mature forest and large trees. New CEs such as this one risk cutting short public input and conversations that address these difficult topics. In our view, controversial projects necessitate a thorough public input process, where stakeholder concerns can be addressed early on, if these projects are to move forward without future challenges.

The appropriations bill also includes funding for fighting wildfires. Intense wildfire seasons over the last years have rapidly depleted the Forest Service’s budget because of “fire borrowing.” Fire borrowing occurs when the Forest Service maxes out on funds allocated for fighting wildfires and the agency uses money from other accounts. By taking money from other accounts to fight fires, the Forest Service delays other projects, including those that support recreation and restoration. The wildfire funding fix passed as part of the appropriations bill includes a cap on the Forest Service’s wildfire suppression budget and establishes a $2.25 billion emergency fund for the agency to use instead of borrowing from other programs. These changes will go into effect in fiscal year 2020, and will help the Forest Service retain funds for ecological restoration and recreation services in future years.

Secure Rural Schools (SRS) payments to counties were also extended for two more years. The Secure Rural Schools Act, passed in 2000, provides funding to rural counties and schools located near national forests. Prior to SRS, rural counties and schools received 25% of revenues generated from timber sales on national forest lands. Unfortunately, SRS payments have not always been consistent due to delays in reauthorization by Congress, forcing small communities to operate on smaller budgets. Extending SRS payments for two more years fixes the immediate problem, but a long-term solution is needed for this program that benefits local communities, forests, wildlife, and recreation.

Additional provisions impacting public lands in the appropriations bill include overriding a Ninth Circuit Court decision that required the Forest Service to re-initiate Endangered Species Act consultation with the Fish and Wildlife Service for land and resource management plans. Also, the bill does not include separate funding for the Legacy Roads and Trails program, which was previously funded at $40 million. The Legacy Roads and Trails program has funded road decommissioning, road maintenance and repairs, and removal of fish passage barriers. LRT has benefited aquatic wildlife throughout our national forests, and we are concerned that this program will not be utilized to its full potential without a budget separate from other Forest Service road programs.

Appropriations and other must-pass legislation can become a battleground for public lands, and we will continue to oppose under-the-radar attacks on our bedrock environmental and public participation laws. For further information about the appropriations bill and related public lands issues visit the links below.

• 2018 Appropriations Bill: “Is This Any Way To Drive An Omnibus? 10 Questions About What Just Happened” –NPR

• Wildfire Funding Fix and new Categorical Exclusion: “The Energy 202: Congress finally found a new way to fund wildfire suppression” – The Washington Post

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”161″ img_size=”full” onclick=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Forest Collaborative Groups

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]In forest collaborative groups, diverse stakeholders including environmental organizations, timber companies, recreational organzations, and other interested members of the community come together to discuss timber sales and other proposed projects with Forest Service staff. Cascade Forest Conservancy is a founding member of, and active participant in, both forest collaboratives in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. The Pinchot Partners, formed in 2003, focuses on projects in the Cowlitz Valley Ranger District, and the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative, formed in 2011, focuses on projects in the Mt. Adams Ranger District. Through collaborative participation, our goal is to influence GPNF projects to be sustainable for wildlife, fish, water quality, and local communities.

During the warmer months our meetings involve field trips where we can see proposed sale units or projects after they are completed. Seeing how projects look on the ground inspires robust conversations about topics such as riparian habitat, harvest practices, and roads. Last year, the SGPC went on a trip to a temporary road that had been used in a timber sale and obliterated. Seeing this former temporary road led to a discussion about the impacts of temporary roads that is ongoing. The Pinchot Partners visited units for the Iron Crystal timber sale and areas that would be part of huckleberry monitoring efforts. During the huckleberry trip, Pinchot Partners members were able to learn about our huckleberry monitoring process from CFC staff.

During the warmer months our meetings involve field trips where we can see proposed sale units or projects after they are completed. Seeing how projects look on the ground inspires robust conversations about topics such as riparian habitat, harvest practices, and roads. Last year, the SGPC went on a trip to a temporary road that had been used in a timber sale and obliterated. Seeing this former temporary road led to a discussion about the impacts of temporary roads that is ongoing. The Pinchot Partners visited units for the Iron Crystal timber sale and areas that would be part of huckleberry monitoring efforts. During the huckleberry trip, Pinchot Partners members were able to learn about our huckleberry monitoring process from CFC staff.

Another important role of the collaborative groups is to vote on retained receipts funding. This is money generated from selected timber sales that is used to fund restoration activities. Both collaboratives get to vote on our priorities for restoration activities and how much funding should be allocated to these projects. The collaborative groups have chosen to fund high school field work crews, aquatic restoration projects, riparian planting, invasive weed treatments, and many other projects through retained receipts.

Over the last year in the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative we have worked on the Upper White Salmon timber sale, formed subcommittees to focus on important topics, and began discussing the Middle Wind timber sale. The Upper White Salmon project was located in drier forest near Mt. Adams. A focus of the collaborative discussion in this project was the harvest prescription for mature forest units with large trees. After several meetings we were able to reach a compromise that considered wildlife habitat, the role of fire on the landscape, and the future climate change impacts. The Middle Wind project is located in a part of the GPNF that has many riparian areas and listed fish habitat. We would like to see this project implemented in a way that improves aquatic habitat and reduces road mileage in the watershed. We have also participated in subcommittee meetings to develop a Zones of Agreement document for the group focused on plantations. The intent of that document is to streamline discussion for topics we agree on, and to educate others about the SGPC.

Over the last year in the South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative we have worked on the Upper White Salmon timber sale, formed subcommittees to focus on important topics, and began discussing the Middle Wind timber sale. The Upper White Salmon project was located in drier forest near Mt. Adams. A focus of the collaborative discussion in this project was the harvest prescription for mature forest units with large trees. After several meetings we were able to reach a compromise that considered wildlife habitat, the role of fire on the landscape, and the future climate change impacts. The Middle Wind project is located in a part of the GPNF that has many riparian areas and listed fish habitat. We would like to see this project implemented in a way that improves aquatic habitat and reduces road mileage in the watershed. We have also participated in subcommittee meetings to develop a Zones of Agreement document for the group focused on plantations. The intent of that document is to streamline discussion for topics we agree on, and to educate others about the SGPC.

This year the Pinchot Partners drafted a response to the Iron Crystal Environmental Analysis and developed a huckleberry restoration strategy in partnership with the Forest Service, CFC, and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe. The Iron Crystal response required several long phone calls and in-person meetings to work through the range of values at play in this project. Many of us shared concerns with the analysis prepared by the Forest Service and met with local Forest Service staff to discuss these issues. We were successfully able to submit a letter before the comment period deadline. In addition to our role as a board member of the Pinchot Partners, CFC also began a new partnership with the collaborative through our huckleberry monitoring. Huckleberry is an important plant to the region culturally, recreationally, and economically, and the Pinchot Partners decide huckleberry restoration should be a priority concern for the organization in the coming years. On February 27-28 the Pinchot Partners held their annual meeting in Packwood, WA. The day and a half meeting is full of great discussions and presentations with Forest Service staff, and this year we visited the White Pass Country Museum and learned about the history of the local communities. Last year, the Pinchot Partners celebrated their 15th anniversary. Over the last fifteen years, our dedication to working together on forest projects has made the partners an example for other collaborative groups throughout the region.

Finding common ground can sometimes be slow, challenging work. It often requires balancing environmental, economic, cultural, and recreational concerns and reconsidering what success means for each of us. Successful collaboration relies on a diverse group of stakeholders, representing a full spectrum of user groups, and bedrock environmental laws. Attempts to weaken environmental laws by Congress present a direct threat to the progress collaboratives have made toward rebuilding trust and developing projects that benefit forests and communities. We are encouraged by the progress these organizations have made since their formation, and we look forward to working on future projects together.

Finding common ground can sometimes be slow, challenging work. It often requires balancing environmental, economic, cultural, and recreational concerns and reconsidering what success means for each of us. Successful collaboration relies on a diverse group of stakeholders, representing a full spectrum of user groups, and bedrock environmental laws. Attempts to weaken environmental laws by Congress present a direct threat to the progress collaboratives have made toward rebuilding trust and developing projects that benefit forests and communities. We are encouraged by the progress these organizations have made since their formation, and we look forward to working on future projects together.

Both collaborative groups meet monthly, and the meetings are open to the public.

To learn more visit:

South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative: http://www.southgpc.org

Pinchot Partners: https://pinchotpartners.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

With the New Year, Comes a New Project for CFC!

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]Beavers have a bit of a reputation as being nuisances for landowners. But to us, they are self-adapting ecosystem engineers! For that reason, we are beginning a project with Cowlitz Indian Tribe to reintroduce more beavers into the aquatic ecosystems of Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Beavers are able to build resilience to climate impacts, create wetland and side-channel habitat, and improve water quality for downstream communities. In the face of climate change, events like increased winter streamflow and low summer flows and drought, these furry engineers can help mitigate the impacts of fluctuating streamflows. A newly constructed dam will increase channel complexity and forge new routes of flow. This process also helps keep water in the system for longer periods of time and transfers water to wetland areas that could otherwise become dry. Dams can create more deep pools, which is important for many threatened and at-risk fish species that reside in GPNF. All in all, the reintroduction of beavers a unique and self-adapting way to improve aquatic health and enhance resilience to climate impacts we expect to see in the future.

Our goal with the beaver project is to release 18 – 25 beavers over two years into strategic locations in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. To date, we have carried out site visits with Forest Service biologists and Cowlitz Indian Tribe, begun a spatial analysis to identify optimal release sites, worked with specialists concerning pre-release habitat modifications, planted willows for future beaver forage, and set up plans with local hatcheries to serve as holding facilities for the beavers. Beaver speed dating, anyone? In October, our Young Friends of the Forest participants got the opportunity to visit the forest and gather field data to help assess potential beaver relocation sites. As the year progresses, we will continue to assess more potential beaver relocation sites, and once those sites are chosen, the acquisition of beavers from landowners will begin. From there, beavers will be housed for brief periods of time at local hatcheries, set up with a mate (the beavers will have a higher rate of success in a pair), and then released! Keep an eye on our social media for updates throughout the year. A huge thanks to the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation for helping to fund this project, as well as our many project partners – especially Cowlitz Indian Tribe and U.S. Forest Service.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Protecting Key Habitat Areas of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text]From old-growth forests to snow-covered alpine areas, Washington’s South Cascades are home to a variety of habitat types that support a wide array of plant and animal populations. Connectivity throughout the landscape allows wildlife to move between habitat areas, enabling populations to be more resilient to a changing climate. Cascade Forest Conservancy has identified some of the key areas in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest that, with increased protections, would improve and sustain the ability of wildlife populations to move between patches of habitat and be more resilient to climate change impacts. Increased protections for these areas could range from administrative action, which protects a few select ecosystem values, to designation under the Wilderness Act.

Although there are a variety of approaches for mitigating the impacts of climate change, there is one theme that runs throughout: protect land rapidly to buffer biodiversity against climate change. Climate change is already causing a shift in different forest types, and these impacts are likely to continue in future generations. For current habitat to persist as functional habitat in a changing landscape, reserves and protected areas should be expanded.

Protected areas provide a way to improve connectivity across the landscape by reducing road densities, eliminating some harmful human activities, and otherwise making key habitat areas and corridors available for wildlife. Climate change is impacting habitat by causing a shift in forest types and a decoupling of species relationships. Warmer, drier years are beginning to move forest types north and to higher elevations, and these impacts may be long-lasting on the landscape. Some wildlife populations will need to migrate to adapt to these changes. If there is not suitable habitat nearby, or it is not connected by a corridor of dispersal habitat, events such as a wildfire or drought could wipe out populations. By protecting key habitat areas in the forest through laws, regulations, and other designations, we can help ensure that they remain intact to benefit wildlife populations.

Key areas identified for increased protection in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

To identify priority areas for increased protection in this region, we first located roadless areas to determine where connectivity would be improved by maintaining large roadless areas and smaller connected ones. We also focused roadless areas because Inventoried Roadless Areas already receive some protections under the 2001 Roadless Rule and are good candidates for additional protection. Locating roadless areas on a map also helped to determine where remnant road segments could be removed to benefit connectivity across the landscape. Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs) are roadless areas greater than 5,000 acres that have been inventoried by the Forest Service during the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) and other assessments. IRAs meet the minimum criteria for designation under the Wilderness Act and are managed in accordance with the 2001 Roadless Rule.

We also located uninventoried roadless areas, which are areas that are predominately roadless, but were not formally inventoried by the Forest Service. Remnant roads, or roads that are closed but still on the Forest Service road system, remain in some uninventoried roadless areas. These remnant roads and roads that lie between two potentially conjoining roadless areas are top priorities for road reduction. To understand where roadless areas exist in relation to habitat core areas and connectivity corridors, we overlaid maps of connectivity corridors on roadless maps. This helps us determine where to focus our climate adaptation efforts to strengthen roadless values and decrease fragmentation.

Based on these maps, and the need for reserves of different habitat types, we identified the following areas as key places for increased protections in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Some of these areas are suitable for designation under the Wilderness Act, but others may be more suited to being protected administratively such as through special area designation or forest plan amendments.

(1) Trapper Creek Wilderness Addition

The “Bourbon Creek” addition to the north side of the Trapper Creek Wilderness contains healthy stands of old-growth forest, and it is currently part of an Inventoried Roadless Area. This Wilderness expansion would provide an important enlargement of contiguous habitat in the southern Gifford Pinchot National Forest and an additional buffer to the surrounding mix of forest lands subject to timber harvest, encroaching forest edges, and roads. Also, there is a lack of Wilderness areas in the GPNF that are easily accessible from population centers. The Trapper Creek Wilderness is a popular location for day-use backcountry recreation, and expansion will enhance those opportunities while also making more habitat available for wildlife. Wildlife camera surveys have shown this area to be well-used by a diverse set of animals and considering the nearby pressures of urban expansion, logging, and habitat shifts, there is good reason to formally establish protection for this area.

(2) Siouxon Creek

The Siouxon Creek area is home beautiful waterfalls and patches of old-growth forest closely intermingled with post-fire habitat created by the many great fires that swept through this area in the early 1900s. These unique features make this area important habitat for many different wildlife populations. Siouxon Creek is also a popular recreation area, and recreation in this area is likely to increase as the nearby population centers in Southwest Washington continue to grow. This important connectivity corridor and popular recreation area would benefit from formal administrative or legislative designation to protect habitat values.

(3) Dark Divide

This iconic roadless area is drenched with more lore and wonder than any other part of the Cascades. This area is thought to be home to Bigfoot, and it was once considered to be the likely landing site of D.B. Cooper, who parachuted from a plane in 1971 with bags of stolen money. Not only is the Dark Divide a landscape of legends, it is also highly important as a habitat reserve for its contiguous old-growth forest stands. Unfortunately, the Dark Divide has been filled with the loud and damaging footprint of off-road vehicles (ORVs). Due to the noise and large ruts created by ORVs, terrestrial and aquatic habitat quality has decreased along with the opportunity for backcountry hiking and camping. The Dark Divide has yet to gain a level of increased protection despite its high value as a large reserve of roadless old growth habitat.

These three areas are a subset of the key areas we have identified for increased protection in the GPNF. A large network of protected areas in Washington’s South Cascades is a long-term goal that will involve partnerships, citizen involvement, and various conservation approaches. Designation of these areas requires working on several levels to increase our understanding of needs and optimal routes for building climate resilience in these forest ecosystems. Many of our on-the-ground efforts will be carried out at the local, ranger district, and regional levels. However, it is also important to continue to advocate for strong national policies as many GPNF projects will be implemented based on national policy. Public involvement in these efforts will be critical. We encourage citizens to write, call, or meet with their congressional representatives and Forest Service officials to advocate for the protection of key natural areas. To learn more about these efforts and CFC’s other strategies to promote climate resiliency in the GPNF, check out our Wildlife and Climate Resilience Guidebook, which can be found by clicking [here][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Press Release: Mining Exploration Approved Near Mount St. Helens

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_separator type=”normal” color=”#444444″ thickness=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][vc_column_text]FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 23, 2017

CONTACTS:

Nicole Budine, Policy and Campaign Manager, Cascade Forest Conservancy, 607-735-3753

Matt Little, Executive Director, Cascade Forest Conservancy, 541-678-2322

Tom Buchele, Managing Attorney, Earthrise Law Center, 503-768-6736

Steve Jones, Board Member, Clark-Skamania Flyfishers, 360-834-1265

Kitty Craig, Washington State Deputy Director, The Wilderness Society, 206-473-2523

Mining Exploration Approved Near Mount St. Helens

Conservation and Recreation Groups Oppose Due to Impacts on Fish, Water Quality and Recreation.

Portland, OR – On August 22, 2017, the Forest Service issued a draft decision consenting to exploratory drilling in the Green River valley, just outside the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. A coalition of over 20 conservation and recreation groups opposes the project, claiming mining exploration and development will significantly harm wild steelhead populations in the Green River, destroy recreational opportunities in the area, and pollute the water supply of downstream communities. The draft decision begins a 45-day objection period.

“Tens of thousands of people have expressed opposition to this proposal due to its impacts on clean water, native fish, and recreation in and around our most treasured National Monument. Yet the agencies continue to advance this dangerous proposal,” said Matt Little, Executive Director of the Cascade Forest Conservancy. “Allowing mining activities in a pristine river valley alongside an active volcano is simply ludicrous. We will do all we can to stop it.”

Drilling permits would allow a Canadian mining company, Ascot Resources Ltd., to drill 63 drill holes from 23 drill pads to locate deposits of copper, gold, and molybdenum. The project would include extensive industrial mining operations 24/7 throughout the summer months on roughly 900 acres of public lands in the Green River valley, just outside the northeast border of the Monument. The prospecting permits allow for constant drilling operations, the installation of drilling-related structures and facilities, the reconstruction of 1.69 miles of decommissioned roads, and pumping up to 5,000 gallons of groundwater per day.

Some parcels of land in question were acquired to promote recreation and conservation under the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act (LWCFA). In a previous lawsuit filed by the Cascade Forest Conservancy (then the Gifford Pinchot Task Force), a federal judge invalidated Ascot’s drilling permits and held that the agencies violated the LWCFA by failing to recognize that mining development cannot interfere with the outdoor recreational purposes for which the land was acquired. The decision by the BLM and Forest Service to once again issue Ascot drilling permits follows the release of a modified EA earlier this year, prepared in response to this prior court decision.

“This project would severely impact recreation opportunities due to noise, dust, exhaust fumes, lights, vehicle traffic, the presence of drill equipment, and project area closures,” said Tom Buchele, Managing Attorney of the Earthrise Law Center. “I cannot fathom how the Forest Service could legally conclude that drilling would not interfere with recreation without violating the LWFCA.”

The pristine Green River flows through the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, passing through old growth as well as a unique post-eruption environment that provides habitat for a variety of native fish and wildlife. The Green River flows into the North Fork Toutle River and Cowlitz River, which provides drinking water to thousands of people in downstream communities. The city of Kelso recently passed a resolution against the mine because of impacts from leaking mine effluent and failed toxic tailings ponds that would result from locating a mine in an active volcanic zone.

“This prospecting is a threat to wild steelhead in the Green River and the rest of the Toutle and Cowlitz River system,” said Steve Jones, Director, Clark-Skamania Flyfishers. “Washington fisheries managers made the upper Green River a Wild Steelhead Gene Bank in 2014 because this habitat offered the best hope for sustaining wild fish in that system. This river drainage needs to be conserved, not exploited.”

“Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is a national treasure that offers a unique recreational and educational experience for visitors in the Pacific Northwest,” said Kitty Craig, Washington State Deputy Director of the Wilderness Society. “Its borders are no place for an industrial mine that will jeopardize the free-flowing Green River, the drinking water of downstream communities, and the wide range of recreational opportunities these lands and waters provide.”

###

PROPOSAL DOCUMENTS:

Modified EA: https://eplanning.blm.gov/epl-front-office/projects/nepa/52147/66795/72638/Goat_Mountain_MEA_20151217_FINAL.pdf

Cascade Forest Conservancy (GPTF) et al modified EA comments: https://cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/FINAL-Goat-Mountain-MEA-Comments_2-4-16.pdf

Forest Service FONSI/Draft DN: http://a123.g.akamai.net/7/123/11558/abc123/forestservic.download.akamai.com/11558/www/nepa/101692_FSPLT3_4050107.pdf

Senator Cantwell Letter to the Forest Service: https://cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Cantwell-letter-to-Forest-Service-Goat-Mountain-Project_3-18-16.pdf

LEGAL DOCUMENTS:

Judge Hernandez’s Opinion: https://law.lclark.edu/live/files/17566-gifford-pinchot-mining-decisionpdf.

MAPS/PHOTOS:

Map of the Project Area: https://cascadeforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Map-of-Mt-St-Helens-mine-area-zoomed-in.jpg

VIDEO:

Cascade Forest Conservancy “Mount St. Helens: No Place for a Mine” : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjVk78cVNCk

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”164,161,145″ img_size=”full” onclick=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Northwest Old-Growth Forests: Carbon Storage Stars

[vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]

By Nicole Budine

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”35px”][vc_column_text]Lush, old-growth, conifer forests are an iconic feature of the Pacific Northwest. Large, magnificent trees and brilliant shades of green bring people from near and far to these forests to recreate. Pacific Northwest old-growth forests are beautiful backdrops for recreation, but they also have an important role in mitigating climate change impacts. The Gifford Pinchot National Forest, which has several areas of low elevation mature and old growth forests, is ranked fourth in the nation for carbon storage. Old forests absorb more carbon than young forests because there is a complex ecosystem, with each plant, animal, and fungi playing a role in carbon storage. As part of our climate resilience blog series, this article highlights information on old-growth forests and carbon storage presented in our Wildlife and Climate and Resilience Guidebook.

Northwest Forest Plan

Northwest Forest Plan

Decades of clearcutting left a legacy of young plantations and fragmented old forests. Logging old-growth forests releases a lot of carbon by cutting old trees and disrupting the diverse ecosystem working to store carbon. Thankfully, old-growth logging on our federal public lands in the northwest was mostly halted by the Northwest Forest Plan, created in 1994 in response to the impact of large-scale clearcutting on the federally-protected northern spotted owl. One way the Northwest Forest Plan changed logging on federal lands was by allocating land for the future development of old-growth characteristics, called Late Successional Reserves, or “LSRs.” Management of LSR forests should encourage the future development of old-growth characteristics including downed logs, standing dead trees called “snags,” and diverse understory plants. By encouraging the development of old-growth characteristics in reserves throughout the region, the Northwest Forest Plan protected entire old-growth ecosystems, not just individual trees.

Recovering the Landscape

Although many old-growth forests are safe from clearcutting today, we still have a long way to go to recover from the mistakes of the past. Connectivity between large, biodiverse areas is important to support long-term ecosystem stability in the face of a changing climate, but decades of clearcutting fragmented mature and old-growth forests. By protecting roadless areas and expanding wilderness areas, we can preserve the high carbon storage potential of remaining old-growth forests and improve connectivity across the landscape. The Northwest Forest Plan provides a framework for encouraging the development of future old-growth forests, but it only applies to federally-owned lands. Various landowners working in partnership to promote the development of mature forests will increase carbon storage potential throughout the region.

Mature forests, well on their way to developing old-growth characteristics, are at-risk in controversial clearcutting projects. Forests that are 80 years or older are often already developing the diversity needed to be valuable habitat and climate refugia. Logging these areas, if done at all, should focus on the development of old-growth characteristics. Commercial logging should focus on thinning plantations to improve diversity, as plantations offer little value for either habitat or carbon storage. Management of forests should look beyond their financial value for timber production and also consider their immense value in mitigating the costly impacts of climate change.

Mature forests, well on their way to developing old-growth characteristics, are at-risk in controversial clearcutting projects. Forests that are 80 years or older are often already developing the diversity needed to be valuable habitat and climate refugia. Logging these areas, if done at all, should focus on the development of old-growth characteristics. Commercial logging should focus on thinning plantations to improve diversity, as plantations offer little value for either habitat or carbon storage. Management of forests should look beyond their financial value for timber production and also consider their immense value in mitigating the costly impacts of climate change.

To learn more about the Northwest Forest Plan and forest management in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, visit: https://cascadeforest.org/our-work/forest-management/[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”grid” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” css_animation=”” css=”.vc_custom_1465592094531{background-color: #96d1ae !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner row_type=”row” type=”grid” text_align=”left” css_animation=””][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”125px”][latest_post_two number_of_columns=”3″ order_by=”date” order=”ASC” display_featured_images=”yes” number_of_posts=”3″][vc_empty_space height=”75px”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]