CFC’s beaver reintroduction program has been operating since 2019 and to date has released 34 individuals into carefully studied and selected locations where the animals have the best possible chance to thrive. We, along with an ever-growing number of Tribes, agencies, and organizations, are using beaver reintroductions as a way to improve degraded habitats and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Watersheds are healthier and more resilient when beavers are present. Their dams slow waterways and create deep pools, expand and improve aquatic habitats, foster drought and flood resilience, and slow or even disrupt the spread of wildfires.

At the end of the third field season in my time working as Cascade Forest Conservancy’s (CFC) Communications Manager, I had an opportunity to participate in and document the final leg of a beaver’s relocation into the forest–something that has been high on my “CFC bucket list” since I joined the team. This was my first chance to meet the iconic, indomitable, habitat-engineering North American beaver (Castor canadensis) up close.

I was also getting time to chat with CFC’s Science & Stewardship Manager/beaver wrangler extraordinaire, Amanda Keasberry, on our drive north to the release site as our passenger, a 55-pound male beaver, napped on a bed of straw in a large animal carrier in the back of the Subaru. Amanda trapped him the day before, and he had spent the night at the Vancouver Trout Hatchery, where animals are safely housed and cared for between capture and release. We are grateful to have access to these facilities thanks to new partnerships with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and our friends at Columbia Springs, a local nonprofit working to inspire stewardship through education experiences designed to foster greater awareness of the natural world.

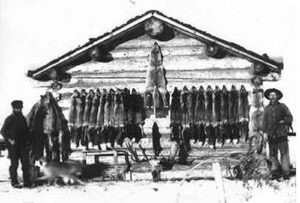

I found it difficult to fully comprehend how it was that animals like the one snoring softly behind me had once been the driver of continent-wide change. Not so long ago, Europe’s obsession with fashionable pelts motivated and financed westward colonization and resulted in the near-eradication of beavers from many parts of North America. The loss of this once-abundant keystone species profoundly altered the character, course, and quality of unfathomably vast areas of aquatic and riparian habitat across the continent. The systematic extermination of beavers was an ecological disaster on par with the destruction of the buffalo herds of the Great Plains.

As we drove, our conversations returned to CFC’s beaver program. Now a licensed trapper equipped with advice from a few generous mentors, Amanda had been busy, to say the least. Our passenger (the mate to a beaver caught earlier in the week) was the sixth animal Amanda had successfully trapped in only ten days. These two beavers, she explained, were being moved at the request of a local landowner. It seemed that after several years of peaceful co-existence, the situation with these beavers had become dangerous. The landowner had noticed that the animals had been chewing large trees on a slope directly above their home. Just days before traps were set, the beavers felled a tree onto the homeowner’s deck. “A lone beaver can take down a large tree in a single night,” Amanda explained.

Nearly all of the beavers CFC relocates come from similar situations. Although current population numbers are still well below their estimated abundance prior to European colonization, the species has managed a remarkable recovery. Unfortunately, they have been slow to return to some areas high in watersheds where their dam-building will have much-needed positive impacts. The species is, however, becoming widespread in some places where their tendency to down trees, flood fields or roads, or block culverts, inevitably leads to conflict with human neighbors. Even ardent lovers of wildlife sometimes feel forced to resort to lethal removal. Thankfully, Amanda’s trapping and relocation efforts provide an alternative. In many instances, beaver relocations represent the best outcome for all involved.

As we neared our destination and gained elevation, the rain picked up and the temperature dropped. We stopped along an unpaved forest road south of Mount St. Helens. After zipping up our coats, pulling up our hoods, and putting on gloves and waders, we carried our cargo (who was still somehow napping) into the brush before carefully lowering the carrier to the ground a few feet back from the bank of the waterway.

I could tell from the animal carrier-sized depression in the grass and the bits of straw on the ground that this was exactly the same site where this individual’s mate had been released just days before. Amanda noted that the willow trimmings she’d left on the bank had been eaten. This was a good sign, she said. She felt reasonably optimistic that our male’s mate was still nearby.

I expected our beaver would be eager to get away from us, his strange captors, as soon as the door to the carrier opened. I walked off a few yards to set up a camera and tripod and prepared to capture what I thought would be a quick burst of action. I hit record and gave Amanda a thumbs up. The door swung open, but to my surprise, nothing happened. This male was in no hurry to leave. It seemed he’d prefer to continue contentedly napping on his warm bed of straw.

Amanda coaxed him out by gently lifting the back of the carrier up a few inches. Still, even on the bank, the beaver was in no rush to go anywhere. But a minute later, his nose began to twitch–he seemed to smell something familiar. He zeroed in on remnants of the bedding left behind from the earlier release of his mate and started to perk up.

At last, the beaver was on his way. He lumbered a few feet down the bank before slipping silently into the dark, tannin-stained waters. Watching him go, I had thought he was slow and awkward on land. Once in the water, however, he moved gracefully and with purpose.

He swam for a short distance with his head and back above the surface, then arched his back and slipped out of sight beneath the water–becoming in that instant as much a part of this landscape as the grasses, willows, and western redcedars around us. I was moved to see him set off into this wild, remote, and unnamed waterway deep in the forest, and felt hopeful in the understanding that if all goes well, the presence of this beaver and his mate will improve this area and protect it from the worst impacts of climate change for years to come.