As we come to the end of Women’s History Month, we reflect on the women who have led the fight for conservation in the southern Washington Cascades and who shaped our history as an organization.

We asked questions to three leaders: Susan Saul, who fought for the protection of Mount St. Helens and was a leader and co-founder of the Gifford Pinchot Task Force (now Cascade Forest Conservancy); Susan Jane Brown, an environmental lawyer and the Task Force’s first Executive Director; and our current Executive Director, Molly Whitney.

(Responses have been edited for clarity and length)

What first led you to pursue a career in conservation?

Susan Saul:

I grew up in Oregon. We lived “out in the country” so I spent a lot of time outdoors and my parents took the family camping in the Cascades and at the Oregon Coast for vacations. When I was 15, I went on my first backpacking trip and was introduced to hiking and wilderness camping. By the time I entered university, I knew I wanted a career that involved both writing and the outdoors. I met a woman who was the public affairs officer for the Willamette National Forest and she mentored me with advice regarding which classes to take. I graduated with a degree in Journalism with an unofficial minor in environmental education and interpretation.

I worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for 33 years in a variety of public engagement jobs, mostly with the National Wildlife Refuge System, so I had a paying career by day and a separate volunteer “career” by night and on weekends.

Susan Jane Brown:

I grew up in a family that spent a lot of time in the out-of-doors, camping, hunting, fishing, so the environment was always something that was important to me. I also always wanted to be a lawyer, and in high school and college became aware that there was a discipline of law called environmental law. I set my sights on environmental law, and thus wanted to attend Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, which is the number one environmental law school in the country. It was only once I got to law school that I fully came to understand the nature of public interest environmental law, which is what I practice today.

Molly Whitney:

Being a born and raised Portlander, I think an appreciation for the natural world is in my blood. Also, my father is a biologist and learning about the ecosystems around me was a part of everyday conversation. I grew up on a trail or in a canoe exploring the world around me – rain or shine. I saw negative impacts of development and human interference, but also noted that there were many groups working to stop and or mitigate these impacts… I knew which side I wanted to work for.

Was there someone or something that inspired you to become a leader in the field?

Susan Saul:

I moved to Longview, Washington, to take my first permanent job. I joined the local Audubon chapter and the Mount St. Helens Hiking Club to find like-minded people for outdoor recreation. Quickly, older members introduced me to conservation issues in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest (GPNF), particularly around Mount St. Helens. I spent most of my free time hiking, backpacking, and scrambling with them so I got to know the places as well as the issues.

In the autumn of 1977, I saw a newspaper notice that a group called the Mount St. Helens Protective Association was holding a public meeting. I attended the meeting and joined the group. Local hikers, backcountry hunters and equestrians had formed the group in 1970 to seek national monument designation for Mount St. Helens but they hadn’t achieved much public or political traction. I had some ideas to build public support so I gradually took on a leadership role.

I was mentored by Joe Walicki, Northwest Representative for The Wilderness Society, Helen Engle of Tacoma and Hazel Wolf of Seattle, founders of many Audubon chapters in Washington state. Joe prodded me to get newspaper coverage for the Mount St. Helens monument proposal and to make my first constituent visit with Congressman Don Bonker of Washington’s 3rd District.

I attended the twice yearly Audubon Council of Washington meetings where I got to know Helen and Hazel and made presentations on conservation issues in southwest Washington. By the time Mount St. Helens erupted in May 1980, I had established recognition as a local conservation leader. State-wide conservation groups turned to me for leadership regarding how the conservation community should respond to the eruption.

Susan Jane Brown:

I never intended to be “a leader,” but rather I love my job and the work that I do. I guess that passion and excitement is attractive to others, who want to share in that energy. I’m glad that I have partners who I get to work with that also inspire me to protect the wild places and critters that I love.

Molly Whitney:

I’ve been influenced by strong women in my family – to become a leader in any field. My grandmother earned her PhD when it was nearly unheard of for her generation… and my mother earned her MD. Matriarchs have led our family – they demonstrated that there is nothing that couldn’t be achieved if you worked for it and gender should never be a limiting factor.

Susan, as you mentioned, you were an important part of the Mount St. Helens Protection Alliance that predated the creation of the Gifford Pinchot Task Force (which you went on to help establish). Susan Jane, you were the first staff person/Executive Director of the GPTF. What are the biggest changes you have noticed about conservation in the Pacific Northwest over your careers?

Susan Saul:

Women have always played a leadership role in conservation in the Pacific Northwest, but they had to fight for recognition of their skills and abilities. Men always wanted all the glory and tried to delegate women to making coffee and taking meeting minutes. I almost quit the entire conservation movement after three men from state conservation organizations drove down from Seattle, accepted my hospitality and proceeded to dictate to me a long list of tasks that I should do, without any offers of help, and unwillingness to acknowledge that I also had a full time job. By the end of the meeting they had me in tears. I called Helen Engle, who advised me: “Susan, just keep doing what you are doing and eventually they will recognize that you know more about Mount St. Helens than they do and they will leave you alone.”

Following passage of the Mount St. Helens Monument Act, my conservation leadership rolled over into working on the Washington Wilderness Act of 1984. I helped craft the campaign that was put together under the leadership of the Washington Wilderness Coalition (now Washington Wild) which was co-founded by a woman – Karen Fant. Many women were leaders in advocating for wilderness in their local areas.

In 1984, the GPNF began work on its land management plan. I organized a meeting of representatives of all the interest groups in early 1985 to figure out how we wanted to deal with the planning process. At the end of the meeting, the group decided we needed a new, temporary organization to lead through the process and chose the name Gifford Pinchot Task Force (GPTF). Five years in, the GPTF had come up with innovative ideas, like creating our own alternative forest plan and getting it included in the Environmental Impact Statement. We had also been appealing timber sales and getting involved in other management issues so it made sense to keep the organization going.

I stepped down from leadership of the GPTF in 1993. By then, women were much more common as both volunteer leaders and paid staff for conservation groups.

Susan Jane Brown:

Probably the biggest change has been the focus of the United States Forest Service. When I started out, the agency was still clear cutting old growth in the Pacific Northwest, and despite the adoption of the Northwest Forest Plan, didn’t show signs of slowing down. Now, a couple of decades on, the Forest Service has really turned a corner with respect to old growth logging: while it sometimes still happens, the agency is much more focused on restoration and collaboration rather than controversy and conflict.

Molly, why CFC?

Molly Whitney:

The forests of the Pacific Northwest are iconic. I spent time in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest growing up… and I had no clue that these beautiful areas that I was experiencing were connected by being within the same National Forest boundary. I can’t remember when I was first introduced to the Task Force, but they, and then CFC, had been on my radar for a long time. When the posting for an Executive Director appeared, I jumped on the opportunity to be a part of this long-standing and impactful organization.

Susan and Susan Jane; what excited you about where CFC is right now?

Susan Saul:

I am enthused by the continuing legacy of womens’ leadership of CFC, including not only Molly as the Executive Director but also the strong supporting roles of Lucy as the Conservation Policy Manager, Amanda as the Stewardship Manager, and Suzanne as the Restoration Manager. I think it is especially important that CFC has expanded its organizational role beyond conservation to also engage in stewardship and science and to partner with the Forest Service on shared projects and goals.

Susan Jane Brown:

CFC is in an interesting place right now: it is an organization that is changing and growing and has a lot of opportunities before it. I’m excited to see how CFC evolves and grows in the years ahead!

What do you see as the greatest opportunities for conservationists working in the Pacific Northwest in the next 5 years?

Susan Saul:

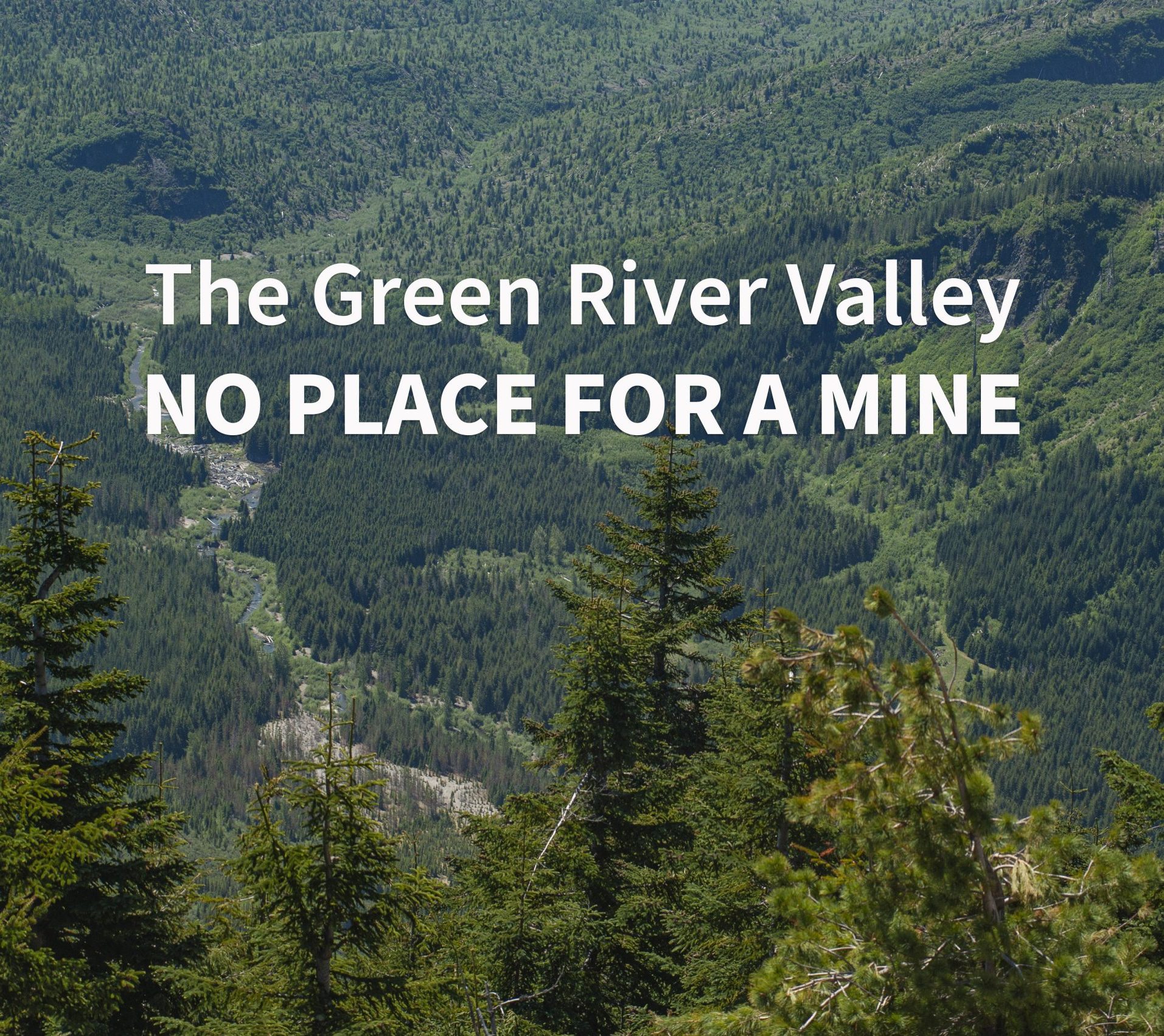

The “30 x 30” conservation target embraced by the Biden administration to protect 30 percent of U.S. land and coastal seas by 2030, with expanded funding opportunities coming through the Land and Water Conservation Fund and other programs. This target and associated funding may bring renewed energy to conservation campaigns like permanent withdrawal of the Green River area from mineral exploration and development and federal acquisition of the High Lakes area northwest of Mount St. Helens.

Susan Jane Brown:

As the Forest Service has shifted away from its commodity production emphasis, the conservation community has a great opportunity to work with diverse stakeholders to develop a new vision for our national forests. In particular, the Northwest Forest Plan is scheduled for revision beginning this year, which means that land managers and the public have the chance to build on the important ecological successes of the Northwest Forest Plan and to address pressing issues such as climate change and wildfire risk reduction. Because forest plans guide subsequent land management decisions, it is essential that forest plans – and the Northwest Forest Plan that covers the range of the northern spotted owl – contain requirements and limitations that will deliver those societal values. But we won’t receive those values without engaging and putting forward a proactive vision, which takes time and intention.

Molly Whitney:

Maybe I’m an optimist but I think that institutions are seeing some of our policies and law as dated and/or needing revision. Take the Northwest Forest Plan. I think we have opportunities to make contributions for the betterment of these policies as they are revisited. We have seen what doesn’t work – we, as conservationists, with growing public support, are situated to address them.

What do you see as the greatest threat we will need to overcome?

Susan Saul:

A challenge, rather than a threat, is engaging the political support of Representative Jaime Herrera Beutler where federal legislation is needed to achieve conservation goals, such as a legislated mineral withdrawal for the Green River.

Susan Jane Brown:

Bureaucratic inertia.

Molly Whitney:

There are few places that are left intact and undisturbed by human interference. I think that these places, unless protected, are on the verge of being lost forever. We can always work toward restoration, but you only have one chance to protect something before it is forever altered. I think, as demands on our natural resources continue to expand, that we will have to work even harder to make sure that these rare places aren’t impacted.

What is one insight that you think is unique to being a woman and a leader in the conservation movement?

Susan Saul:

About 10 years ago I was interviewed for a book, “Extraordinary Women Conservationists of Washington: Mothers of Nature.” My interviewer, Raelene Gold, asked me that same question and we discussed it at length since women’s contributions have until recently been literally left out of important conservation histories. We agreed that women often are more collaborative in their approach to achieving shared goals: women frequently have strong people skills, are more inclusive, listen more, read situations more accurately, and are more likely to build teams to solve problems. They learn from adversity, often with an “I’ll show you” attitude.

Susan Jane Brown:

As a woman in a male-dominated field (both conservation and law), I frequently see and feel the power imbalance inherent in my work. Once you are attuned to that inequity, you see it everywhere and want to address it, but systemic inequality cannot be solved by one person alone, but rather by the whole community sharing power. Getting the message across that the conservation community is stronger when we share power, rather than by treating conservation as a zero sum game where some win and some lose, is a challenge. But working with others who understand this dynamic and are also working to build power by sharing it is incredibly rewarding.

Molly Whitney:

There are new perspectives that can be brought to the conservation movement by people that haven’t been historically represented. There are many voices that need to be heard and I hope that women, as well as many other underrepresented groups, are finding their voices heard and recognized as the movement expands and becomes more diverse.

What advice would you give to girls and women interested in pursuing a career fighting for the natural world?

Susan Saul:

Don’t reject volunteering. I have never been paid for any of the 45 years of work I have described in this interview. There weren’t many paying jobs with conservation groups when I was starting out, and the few jobs that existed paid very little. Joe Walicki, the Northwest Representative for The Wilderness Society in the 1970’s, could not afford to own a car so he traveled around Washington and Oregon by Greyhound bus, couch surfed at the homes of conservationists, and relied on supporters’ generosity for meals and rides.

Find mentors. Take advantage of internships, temporary and seasonal jobs to explore your career calling.

Susan Jane Brown:

Develop a thick, but compassionate skin. Conservation is a full-contact sport, and the losses are tragic: a special place is irreparably changed and perhaps lost, or a species is harmed, or water quality is degraded when our campaigns aren’t successful, and that hurts. Sometimes people operate from a place of fear and are unkind to others who are also working to conserve nature, even though we’re all on the same side, and that hurts. But take comfort in the wild, because it appreciates your efforts, and in like-minded advocates, because they do too.

Molly Whitney:

Do it. If you find a connection, interest, or passion stemming from something in the natural world – follow it. You will be fulfilled if you are following something you love. Challenge the status quos and don’t be afraid to ask why things have been done a particular way… just because they’ve always been done one way doesn’t mean they should continue. Speak your mind, learn from those around you, and change the landscape in which you work and live.